My Life in the 55th Armored Infantry Battalion

by Homer Olson, Company B

On December 7, 1941, came the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. This changed everything for the whole world and us. Our government rationed many things to the civilians; every thing went to the military.

In March 1942, I went to work for the northern oil pumping wells with Ralph Bennett. That was a good job and we got along well together. Many of my friends were volunteering and being drafted into the military. I don’t like water, so I didn’t want the Navy. Because of my bad ears, I couldn’t get into the Air Force. So I waited for the draft. I turned twenty years on September 15,1942.1 was put in class 1 -A and passed my physical in Erie, Pennsylvania on November 4.1 left on the train November 18, from Ridgeway, Pennsylvania because we lived in Elkco. That day, I kissed my mother and hugged my dad for the first time in my adult life. It was a sad day for them and for all of us. Our induction center was at New Cumberland, Pennsylvania. We were there for three days getting our uniforms, shots, and etc. We were put on a train and four days later we were in Camp Polk, Louisiana. It was a big camp, with two armored divisions there. I was assigned to Company B. 55th Armored Infantry Battalion that I stayed in for the next three years. (They broke us up in August 1945 down in Austria).

We took four months of basic training, there at Camp Polk, and then went on the Louisiana maneuvers for two months. It was pretty rough on most of us – we were busy all the time. We learned to shoot and qualify with the M-l rifle, all of the machine guns, pistol, mortar, hand-grenade and etc. We did a lot of close order drill and many road marches. The longest was a 30-mile hike, with light packs. I didn’t like the bayonet drill and was glad that I never had to use one.

The weather was wet and chilly there and 1 caught a cold and high fever. They put me in the hospital for a few days. That is where I spent Christmas of 1942. We learned a lot in those first few months. A big thing was learning to live together in close quarters. Most guys were great, but there are always a few “bastards.” Some got homesick. I never did, but did get lonesome some times.

About once a month, everyone got kitchen, police, latrine duty and a twenty-four hour guard duty. This is where I learned to clean toilets. On one wall there were three long urinals. Another wall was the sinks and mirrors and on another wall were ten commodes. The showers were back in farther. That place was a madhouse. Every morning, after breakfast, you had no privacy and you couldn’t be bashful. Each company had their own bugler and all the calls were with a bugle. Reveilles, chow call for three meals, and work calls at 8:00 AM and 1:00 PM. Retreat at 5:30 PM and lights out at 9:30 PM with Taps at 11:00 PM. We got up at 5:45 each morning and breakfast was at 7:00. In that hour and fifteen minutes you got dressed, stood reveille, made your bed, mopped the floor around your bunk, made sure your clothes were okay and shoes shined, and fifteen minutes of calisthenics. It sure was a different life style, but it went pretty well if you made up your mind to it. I got a ten-day leave and came home in April after the Basic Training was over.

Pay day was the first day of the month. Fifty dollars in cash was what you got paid. After deductions of insurance, bonds, and laundry, $35.25 was left. Sometimes they would pull a “short-arm” inspection on pay day. This was to check for venereal diseases. The uniform for that hour was shoes and raincoats. A doctor would be sitting on a chair in our day room. We lined up outside and when you got in to see him you opened you raincoat and squeezed you penis. If there was any fluid, you went on sick call and didn’t get paid.

In May and June we were on maneuvers in Louisiana and West Texas. Lots of mosquitoes, snakes and dust. When this was over, we moved to Camp Barkeley, Texas near Abilene. I was assigned to a half track there and became a driver. I liked this better, as I always liked to drive anything. That fall, I was sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky to mechanic school for three months. Gene Foster of B Company 55th AIB was also there and we got to know a couple of girls in Louisville. We would see them on weekends, sometimes.

While we were in Fort Knox, the 11th Armored Division moved to the Mojave Desert near Needles, California for desert maneuvers. When we were done with school, I got my papers, train ticket, and also a five-day “delay in route”, so I went home for three days. On Christmas Day of 1943,1 was on the train headed for Needles. We finished maneuvers in February and went to Camp Cooke, California near Santa Maria. We went to Los Angeles and Santa Barbara some weekends. Usually, we went to Santa Maria. Many of my friends were Italians and we would go to Santa Maria for Italian food on Saturday night and then to the Palamino Bar. If we didn’t catch the bus back to Camp, we would sleep in the USO Club on a pool table or a chair.

Early in September, we were put on a troop train headed for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey and then overseas. That was a nice train ride. It was a long train with two steam engines on front and five steam engines pushing in the rear. We went through thirty-seven tunnels, going from California to Denver. There were two kitchen cars in the middle of the train. The front one served the front half of the train and the back car, the back half. We ate well, two times a day. They stopped once a day and we got off to walked and exercise. It took six days and five nights to get to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. After a few days passed, we went by train to New York and on to a ship, the USS Hermitage. It was an experience, having your name called and walking up the long “gang plank” and knowing that you were leaving your homeland. The duffel bag that we carried was quite heavy. They put us on a deck down below the water line. It was crowded. The bunks were five high. The lights were not bright enough so that we could read a little and play poker and shoot crap. These were on the floor wherever we could find a place to put a blanket down. There were poker games, going on some place, twenty-four hours a day.

There were five thousand of us on this ship and they told us there were sixty ships in the convoy. Each ship was a mile apart so we couldn’t see all of them when we were allowed up on the top deck. We had a Navy escort: the Destroyer Escorts. They would zigzag between the ships looking for submarines. I got a little sea sick at times, but not bad. We got fed twice daily and I could usually eat a little. We ate standing up with our trays on a bar. You had to hang on to the bar, your tray, and hit your mouth with your spoon. The ship was rolling in some direction all the time.

We were thirteen days on the ship and landed in Southampton, England around October 3rd. They put us on a train and took us to a small camp between Tisbury and Hinden, about ninety miles from London. We didn’t do much training in England, just a few hikes now and then. Over a period of time we got our equipment which consisted of tanks, trucks, jeeps, half-tracks guns, ammunition, and rations.

We were given some two-day passes. I went to Bristol once and London twice. One pass that I had to London, was the day before payday and then payday. An English pound was worth $4.09 at that time. The first night that we were there, the price for a woman, all night, was one pound. The next night (payday) the price was four pounds. We didn’t bother the women that night.

Early in December, we crossed the English Channel. The drivers went with their vehicles, tanks, halftracks, trucks and jeeps in a “landing ship tanks” (LST). The front of the LST opened up and we drove up into it and turned around so that you faced out. This way you could drive straight out onto the beach when they opened up. We were on this ship for twenty-four hours and landed near Cherbourg, France. We drove to fields near Rennes, France. It took three days for our division to assemble there.

That night, out in the channel, there was a submarine alert. They stopped the ship and killed the engines. We were “bobbing” around out there in that flat bottom ship. Each driver had to pull a two-hour fireguard in the tank deck with a guy on each end. My time was midnight to 2:00 am. It was hot down there and very strong gasoline fumes. I got seasick and “threw-up” a few times, until there was no more to come up and I just “gagged”. I was sure glad when 2:00 am came so I could lie down again.

After the division got all together, we started to move inland. Then an order came down to change course and go North. When we got up to Rhiems, France we heard about the German breakthrough in Belgium – making what they called the “Bulge”. We hit snow and cold weather up there. From here on things and places are vague and hazy. I know that we spent Christmas day in Belgium somewhere. It was cold.

We were in reserve for a couple of days and then they gave us a small town to take. We didn’t get it that afternoon. We had a counter attack that night and the Germans took nineteen guys from our company prisoner. I remember that one guy was taking twelve German prisoners back and one was wounded and couldn’t walk fast enough, so he shot him there on the road. I thought to myself “what the hell is going on here? This is terrible”. After awhile, you get used to these things and if you want to survive you can become pretty cruel.

The Germans had Bastogne surrounded for many days. Most of the 101st Airborne Division was in there. The 4th Armored got in there first from the south. We got in a day or two later from the northwest. That was a happy day for everyone.

We started moving again, taking small towns, clearing woods, and slowly closing the Bulge. It was cold and the snow was quite deep. There was lots of frostbite on the fingers and toes. We threw away our shoes and cut up GI blankets into strips about six inches wide and wrapped our feet and legs. We then put our feet into four buckle overshoes, which we had. I went to the Aid Station one time and they painted my toes with something. I just lost a couple of nails. At one time, I had on two pairs of long underwear, two pairs of pants, two shirts, a woolen GI sweater, and a field jacket. It is unbelievable what the human body can stand – both mental and physical. Some people are stronger than others are – so some “broke down” – it was nothing to be ashamed of. I know that prayers helped a lot.

Every letter, that I wrote home, I asked Mom and Dad to send gloves, handkerchiefs, and socks. I carried them in my seat cushion, in my halftrack, and gave most of them to my buddies. They nicknamed me “Mother Olson”. One time, I asked Mom to send us a chocolate cake with frosting and walnuts on top. She did and it came in about five weeks. The walnuts were green with mold, so we threw them away and made quick work of that cake.

I remember one town near Longchamps in Belgium. We got the hell knocked out of us going in. We cleared the town and stayed there that night. The next day was bright and sunny. We could see some dead Germans laying in the snow, up in a field, near some woods. We found a long piece of rope and went up there. There were twelve lying frozen in many positions. Sometimes the Germans would “booby- trap” their dead. We would tie the rope around a leg and drag them a ways and make sure there were no wires attached to the bodies. Then we looked for watches and pistols. I remember one that I rolled over. His face was gone from the forehead down.

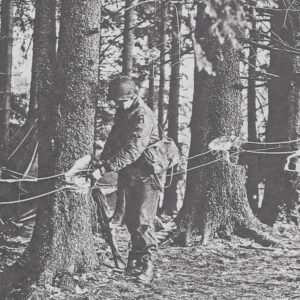

One time, there were several of us “dug-in” along a dirt road, in some woods with lots of pine trees. A jeep came down the road and stopped. It was a Lutheran chaplain from another unit. He asked if we wanted a prayer and communion. Of course we did. We were Catholics, Jews and etc. But it made no difference. We got on our knees in the snow with our helmets on, and weapons slung on our shoulders. He had some bread and bottles of wine and poured the wine in our canteen cup. A few shells landed fairly close but no one ran to their holes. He never stopped pouring the wine. We all felt better after he left.

One time they pulled us back in reserve for a few days. We got some replacements, supplies and hot food from our kitchen. We were “dug in” (two man foxholes). Anderson and I usually dug in together (he was a swell guy). He drove second track and I drove first track. We were getting a lot of artillery and mortar fire. Also, the Germans had a weapon that fired a shell like a mortar or a small bomb. We called them “screaming mimis”. They mostly came at night and scared hell out of you. We were cold, wet and lying in our hole one night when things were coming in pretty heavy. I started to shake and shiver and just couldn’t stop. I said, “Andy, I can’t stop this shaking.” and started to cry. It was all getting to me – especially the cold. Andy held me – lit me a cigarette and we talked. After a while I calmed down. Anderson was a great guy. As were all of our guys,. We loved and depended on each other you couldn’t make it alone,

One night, at this same place, Andy and I were leaning against my halftrack. We could hear a mortar shell coming (they came slow). We didn’t have time to get in our hole, so we dove under the track. The shell landed four or five feet away in the snow and mud. It didn’t explode; it was a “dud”. The book wasn’t open on our page that night. We survived. One afternoon, later on, we had taken this small town and we were getting some machine gun fire from some woods. Our company went to clear the woods and had to stay there all night. They called on the radio to bring up some rations and ammunition. They said the field might be mined. Andy and I gathered up supplies and put half in his track and half in mine. We thought that one of us should get through. We ran side by side and both got through. We tried to follow our same tracks back and about halfway back, Andy hit a land mine with the left track and caught fire. I stopped, he jumped out and ran to me and we made it back.

Somewhere along about this time they had brought up a portable shower unit. They had big tents and many tank trucks with water and it was hot. We went back and got showers and new clothes. Boy, they felt good. We hadn’t taken a shower since we left England two months earlier. That is the only good thing about fighting a war in the wintertime. You didn’t stink much and the dead bodies didn’t stink either because they froze quickly.

We closed the “Bulge” late in January and hit the Siegfried Line in February. The snow was melting and there was lots of mud. I developed a fear and hatred for the snow and cold that winter and it will stay with me forever. After the Siegfried Line, we started the “spearheads” to the Rhine river. Our objective was the city of Andemach, a city north ofCoblenz. We cleared the city with help from another unit.

They then pulled us back a few miles to a small town. We were there five days, while the engineers built a “bailey bridge” across the Rhine. Owens found a German motorcycle there. Each morning, he and I would ride it to Andemach and get wine that we had found in a cellar. We gave wine to anyone who wanted some and it tasted good. The house that our squad took over, to sleep in, had a radio and we heard some music for the first time in nearly three months. (American music from Paris)

They built the bridge across the Rhine under a smoke screen and we crossed it in a smoke screen. An experience that I’ll never forget. We started the “spearheads” again and one time we were cut off for three days. They dropped us supplies from the air. Gasoline was the big item and we go that in thousands an thousands of five-gallon cans. I saw General Patton twice. Once in the “Bulge” and once on a “spearhead”.

We had the Germans on the run now. They were running out of gasoline and food, so they were using a lot of horses to move their guns and supplies in wagons. They were being strafed by aircraft and shelled from our artillery and the roads jammed with dead horses, humans and everything. At times, we could not go around them and had to run over the bodies. On these “spearheads,” we came to and released prisoners from POW (prisoner of war) camps and slave labor camps. These were sorry sights. They were so happy to see us. We knew that the end of the war was getting near, and all of us were praying that we could make it now that we had come this far.

We were in the mountains before we dropped down into Linz, Austria, on the Danube River. A small town, Wegshied, we came to in the afternoon. Lots of SS there and putting up a stiff resistance. We got some houses burning so we could see better, when it got dark, we used our cigarette lighters on curtains and etc. S/Sgt. Elwood G. Cashman, my squad leader, got it here. We felt so bad with the end so near. We finished clearing the town. The next day they sent my platoon (five half-tracks), out on a mounted patrol, down a dirt road for a few miles. We hit no resistance and found nothing. While we were gone, they shelled the town with artillery. Another guy had pulled his half-track under a tree where I had been. He got a direct hit and the halftrack was half-gone. He was lying on the ground dead. I thought to my self “God still has plans for me. That could have been me.”

The war ended for us at Linz, Austria, on the Danube river. It was a beautiful city. In spite of the pain and suffering of a war there is a good side. I had many fine friends while in the military and we had many laughs and good times. This friendship has lasted over the years. We can feel it at our reunions.I must say, that we had fine officers as our leaders. Three of them were killed. Most were wounded. Captain George Reimer, our Company Commander, was and is a good man. I think he was wounded four times.

There was a concentration camp near Linz, called Mauthausen. That was a terrible sight and smelled too. Dead bodies all over and the rest were half-dead. They must have killed and burned thousands of people there. We sat in a field for several days after the armistice was signed on May 8,1945. We started “occupation duty” in a small town, Reid, Austria.

I got a three-day pass to Paris late in may or early June. We went to Munich, Germany by truck and got on the train there. The train was full of GI’s going to Paris or Luxemburg. When we got to Paris, they had a place where they gave each one, with a pass, one carton of cigarettes, soap, razor, toothbrush, toothpaste and a comb. Most of us had our own, so we sold those things to French civilians for a good price. We also had German pistols to sell. I had five. The Frenchmen took us to a cafe where we went back in a comer and piled our pistols on a table and ordered a drink. They were looking over the pistols and the fellow across the table from me (one of us) shot himself in the left hand: They called the military police (MP’s) to take him to the hospital. We gathered up our pistols and got the hell out of there fast. It was illegal to sell these pistols. We went to a Red Cross hotel, got our room, and we never heard anything about it. I had a little 25-caliber automatic, in a shoulder holster, which I wore under my shirt. We weren’t supposed to have concealed weapons, but we weren’t too well liked in Germany. So many of us carried something.

The three of us went to a club, that night. Each of us bought a bottle of cognac and a bottle of champagne at $4.00 a bottle. One of the sergeants got pretty drunk and went with a woman for the night. Baldwin and I went back to our hotel room. We saw the sergeant at noon the next day. He was sick and broke. She had “rolled” him for all his money. We each gave him some money. We saw many of the sights in Paris and had a good time there. One afternoon, I was walking by myself, there was a park and it had benches along the side walk. Two women, professionals, were sitting on a bench. We talked a little and “pidgin English” and I went with the older one to her apartment. We went through a door, into a hallway, and got halfway up the stairs when the front door opened and a man came in. I thought that it might be a “set-up”. I unbuttoned my shirt and took out my little pistol. When she saw it, she got excited and finally got through to me that he lived downstairs. I wouldn’t have shot anyone, but I would have scared someone. Everything turned out okay. She was good and knew her business.

When I got back to my company, in Austria, they were loading up the tanks and half-tracks onto freight cars and shipping them back to France. The 21/2 ton trucks they drove back in convoys. I got in on this and there were two drivers to a truck with an officer in charge of each twenty-five trucks. The convoy stretched out for miles. Weaver and I were together and we were three days getting to a racetrack outside of Paris. We got into Paris again that night and caught the train back in the morning. When we rode trains over there, we rode in 40 & 8 (40 men or 8 mules) boxcars. There were no passenger cars this time. We each carried our own bedrolls and rations.

We were then sent to occupy Friestadt, Austria. There was a “displaced persons” (DP’s) camp there. (people from other countries that worked for the Germans.) They were being sent back to their own countries. Wally Laudert and I got in on one trip that was hauling DP’s to Yugoslavia. There were many trucks and each had two drivers. We went over the Alps into Northern Italy and then into Yugoslavia. Several times a day, we stopped the trucks for “piss call”. This was quite a sight. We unloaded the DP’s in a field, near a town, there Marshal Tito’s troops set up machine guns around the DP’s. We stayed there in our trucks that night and were sure glad to leave the next morning. We made this trip early in July and on July 4th we received snow. The first and only time, that I have gotten into a snowstorm in July.

We now were sent to occupy Ebbenzee, Austria. There was a big POW camp there and we had ninety thousand German prisoners to guard. They had “work details” outside of the Camp each day and my job, on most days, was to go to the main gate and draw and sign for six prisoners. They would go to the “wood yard” and cut firewood all day. They cooked on wood stoves in the camp. I carried a submachine gun and they didn’t offer to run away. They were eating pretty well there. In august 1945, they broke up the 11th Armored Division and we were sent in all different directions to other units. We had been together for three years. Some others and I were sent to Czechoslovakia to a town near Pilsen to the 8th Armored Division where I was there a couple of weeks and then went to

Germany to the 83rd Infantry Division. I was put in a service company of the 329th Infantry Battalion. I was driving a truck again. John Singletary, who was “ration breakdown man”, and I would drive to Deggendorfto the railroad each morning. We picked up the rations (food) for the 4th Infantry Company and deliver them to four different towns, that they were occupying. This was good duty. John and I had our room up over the kitchen. The cooks slept there too. So we always had food like oranges, apples, bread and peanut butter in our rooms. Some women would come each night and if they stayed too late, they would stay all night. Civilians had to be off the streets from 11:00 pm till 6:00 in the morning. This is where a woman slept in my bed, one night, when she stayed too late. I never touched her. She looked to rough for me. When I woke up, in the morning, she was gone. I have told this a few times and people don’t believe it. But it is the truth.

We were being sent home on the point system. So many points for service in the States, months overseas, for each Battle Star (I have three), and etc. Anyway, I had sixty points. The 358th Engineer Battalion was being filled with sixty pointers for going home. So they sent others and me to the 358th in some town in Germany. We did nothing there.

One afternoon, an old man was leading an old skinny horse up the street, followed by some old women, with pails and pans. They went to the town square and killed the horse. They cut it up and divided the meat. I didn’t go up to see this – it wouldn’t be a pretty sight. I am fortunate and thankful that I have never been that hungry. In this land of plenty, most people will say that they wouldn’t do this, or they wouldn’t do that. But that is “bullshit.” This county would be the worst, because we are used to having too much. They would get on their knees or kill for a piece of bread. On the day after Thanksgiving, we started our journey home. We were taken to the “tent city” camps, near Rheims, France. These camps were named after cities in the U.S.A. There were units coming in and going out every day. I went into Rheims a few times. Rheims was pretty well cleaned up by this time. The Rheims cathedral is a beautiful church and wasn’t damaged much. We went in and sat down for a few minutes. We were here a couple of weeks and then were moved to a “tent city” camp near Le Havre, France. This was on the coast. We could look down and see the city and the ocean. These “tent cities” were called “cigarette camps” named after cigarette brands. I’m not sure, but ours was “Lucky Strike” or “Pall Mall”. I still had a couple of extra pistols and sold them here. We were allowed to take one home and they were going to pull a “shake down search” on the ship.

All around these camps were signs that said, “one drip and you miss the ship. So if you got the “clap”, you stayed there for treatment. We had a “short arm” inspection the day before we boarded ship. One day they told us that our ship was in and we would be loading up in a few days. On the afternoon of Christinas Eve, 1945 we went down and boarded ship. No trouble walking up the “gang plank”, this time. The duffel bag was lighter and we were going home. We left that evening and went up into the North Sea and around the north of Scotland. They announced over the speakers that there would be a turkey dinner the next day for Christmas. We hit a winter storm that night and all Christmas Day. So many got seasick and couldn’t eat their dinner. I ate some but not much.

This ship was the SS Argentina. It was a nice ship and not too crowded. There were seven thousand of us on it. Our trip lasted seven days before we reach New York on the morning of Jan 1, 1946. Most of us were on the decks so we could see the Statue of Liberty and watch the tugboats pushing us into the pier. It was quiet and no one around because it was a holiday. Later in the day, we were taken off and put on a train to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey again. From there the train sent us to our “separation centers” in our different states. I went to New Cumberland, Pennsylvania again. There, we were “processed out.” They told me my gums and teeth were bad and if I stayed a few days they would fix my teeth. I said, “give me that honorable discharge and I will get my teeth fixed at home, myself.”

On January 5,1946,1 received my discharge, $300 mustering our pay and train ticket to Kane, Pennsylvania. This ended my short military career, three years, two months, and one day. I wouldn’t take a million dollars for the things that I learned. Things that I saw and did. I learned more about discipline, which we have to have in, our homes our work and ourselves. I rode the train all night to Kane. I got home Sunday morning, January 6.1 surprised Mom and Dad. We were happy and had a good cry.