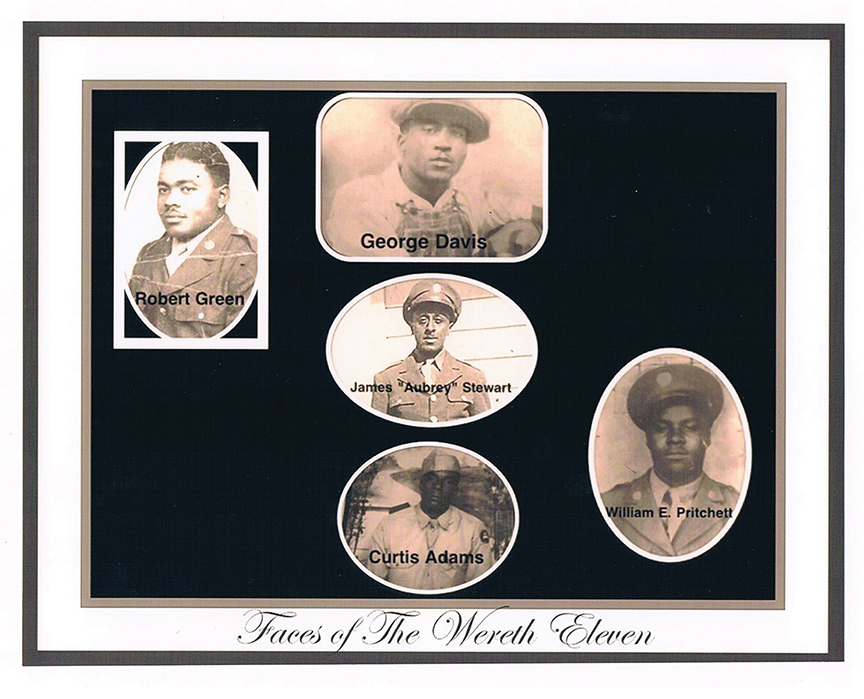

by Sam Schwartz Landrum and Zach Allen Ferdana, Members

Our journey began with a cup of coffee at Le Select, our father’s favorite cafe on Montparnasse in Paris, the city he lived in for 7 years after the war. Allen Schwartz is believed to have landed in Cherbourg on November 2, 1944 and joined his unit, the US 3rd Army, 11th Armored Division, 778th Tank Battalion, Headquarters Company as a reconnaissance scout, in time to leave for Metz to engage in the battle for that city. He was 21 years old. We, his two sons, arrived in Paris on April 5, 2018, more than 73 years later and 25 years to the month after his passing, to begin the first steps of his war journey across the continent. Our plan: to cover the same ground from the coast of Normandy through the Ardennes Forrest to the Rhine River, using his unit’s history and simple hand drawn map marked with his notes.

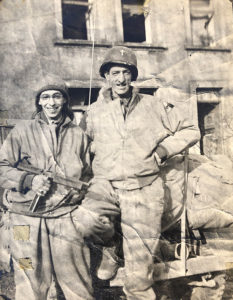

Like many war Veterans, our father spoke little about the war in the days of our childhood, each of us carrying a cloudy memory of half told war stories. However, we can substantiate his presence between the English Channel and the Rhine River during the war in two places: Terville, a small French town north of Metz, on Christmas Day, 1944 and 3 days later, in Uberhern, Germany. Our evidence consists of only two photographs of him during the war itself, from his war scrapbook.

Normandy and Cherbourg: The start of it all

The day after our arrival in Paris, we left for Normandy and moved through history at Sword, Juno, Gold, Arromanches, Omaha, Pointe Du Hoque, and Utah. We also visited Cherbourg, the deep-water port that General Eisenhower intended to capture quickly by adding Utah Beach to the D-Day invasion. It was here that we believe Private Allen Schwartz first landed on the continent on November 2, 1944. He never told us this, but the 778 Tank Battalion landed here in September 1944 and his discharge papers indicate his tour of Europe began on that day in November. Looking out across the port and next to a plaque that acknowledged the port’s “fraternity of arms” from 1914-1918 and 1940-1945, we imagined our father’s first steps of the war, almost 5 months after D-Day. His presence intangible, was it filled with fear and in anticipation of the terror awaiting him?

Metz: “reconnaissance was used

for routes and bridges”

From Normandy we headed to Metz in eastern France, the city where the 778th Tank Battalion first entered combat. Along the way we stopped for the night in Reims to visit the room where World War II Europe ended and surrender papers signed. In Metz we found a lively, industrialized city, our experience and connection to our father increasingly more visceral. Walking the town, it was on a small bridge on the Moselle River that we were struck by our father’s experience somewhere in this city. We pulled out our copy of the “History of the 778th Tank Battalion” we obtained from the US National Archives in Washington DC and read that the battle of Metz in November 1944 was where “reconnaissance was used for routes and bridges.” Moments later, standing on that bridge, we spotted a small plaque commemorating the bridge’s liberation by French forces on November 20, 1944. Was our father, Private Schwartz, here or near here? From the very few stories he told us about the war, he had mentioned being in a reconnaissance unit clearing the way for the tanks of the 778th. He had been in this city, clearing routes and bridges, fighting for his life and the liberation of Europe. Now, on this bridge, we found ourselves closer to his experience decades earlier.

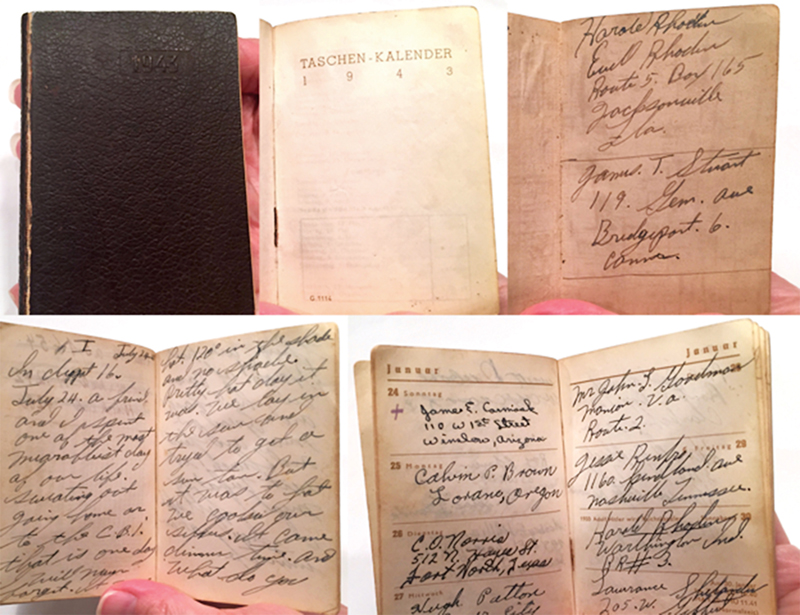

The simple hand drawn map from our father’s war scrapbook was accompanied by the “Vest Pocket History of the 778th Tank Battalion,” a type written listing of the 778th’s war itinerary, dated July 6, 1945. A handwritten note in our father’s writing said that he returned to Paris for a week in late November/early December. We can only wonder what happened and why, after only a few weeks in combat, he went back to Paris and was reassigned as a chaplain’s assistant and driver.

Terville: the search for a school basement

From Metz we drove a half an hour north to Terville to try to find the place where our father’s scrapbook photo was taken on Christmas Day, 1944. Standing beside a Christmas tree with other US soldiers, and French civilians, our father’s handwritten caption is our only clue: “Noel in a school basement. 25 December 44. Terville, France.”

In Terville, we found two schools that survived the war: the Ecole de Musique de Terville and the Ecole Primare le Moulin. We were encouraged to contact the Mayor’s Office to find out more. Because the day was over, we drove to Luxembourg City for two nights to explore and experience the ground of the Battle of the Bulge. Our father wrote that he fought in Luxembourg and Belgium in December 1944 and January 1945. He used to say he fought in the Battle of the Bulge, exactly where and with whom, we do not know. So, we visited the Luxembourg American Cemetery and General Patton’s final resting place, the National Military Museum in Dierkirch, ran a circuit in the hills around Bettendorf and through the southern shoulder of the Bulge marked with old foxholes and GI tree carvings. We also stopped at the General Patton Monument in Ettelbruck, noting that as we follow our father’s footsteps, we follow General Patton’s as well.

The next day we returned to Terville for a meeting at City Hall, where city officials looked at the photo and whisked us into their vehicle to take us to the Ecole Primare le Moulin. They knew instantly which school was the site of the Christmas Day photo. There we met Gilles Leleux, the school’s principal, who welcomed us and led us to the basement where he shared his understanding of the American presence and activity in and around this school during the war. He told us that the school courtyard was filled with American military trucks, and that this basement was where people came when bombs dropped on Terville. Then, what happened next was truly remarkable.

Inspired to learn more, Mr. Leleux made several phone calls and was able to locate a woman who was alive during the war, and she happened to live just two doors down! We entered Ms. Nicolette Zullo’s house with several city officials, the city photographer and Mr. Leleux. She sat on her bed having recently broken her leg. Now in her 90’s, Ms. Zullo looked at our photo, and without hesitation, immediately identified the French civilians as members of the Aime family. She was 17 in 1944, learned to dance from American GIs, told us about how American soldiers first came to Terville, had to leave as the Germans pushed back in, and eventually returned to stay. American soldiers gave the local children candy and gum, she said, and she told of their setting up food lines to feed the local people. She also confirmed that when bombs were dropping, everyone in Terville went to this one school, now the Ecole Primare le Moulin. She did not recognize our father, but remembered Christmas Day in 1944, the lack of food and the miraculous appearance of a turkey in their yard that they captured and ate.

After our visit with Ms. Zullo and our identification of the Aime family in the photo, Mr. Leleux was able to locate and get the youngest daughter of that family on the telephone: Ms. Bernadette Aime, a resident of nearby Thionville. Although she herself was not in the Christmas Day photo, connecting with her brought new life and curiosity into the story behind this photo.

Into Germany: Uberherrn and

the Rhine at Oppenheim

We left Terville as Mr.Leleux worked on setting up a meeting with the Aime family, crossed into Germany and stopped where our father did, in Urberherrn, long enough to pose for a photo much like he did with the chaplain he was assisting. We drove further on, our goal to reach the Rhine and found our home for the night where General Patton and his men first crossed it, at Oppenheim. “The Vest Pocket History” said the 778th arrived at GauOdenheim on March 23, 1945 and crossed the Rhine somewhere close, quite possibly at Oppenheim, on March 25, 1945. We put our feet in the water of the last major barrier to the heart of Germany, watched barges and kayaks float by, imagining American soldiers, and perhaps our father, crossing here. That night Mr. Leleux emailed us to confirm that he had arranged a meeting the very next day back in Terville with Ms. Bernadette Aime, and her granddaughter who spoke English, to look at our Christmas Day 1944 photo.

Terville revisited: meeting

Ms. Bernadette Aime

We arrived early for the meeting at the Ecole Primare le Moulin. Mr. Leleux greeted us then took us down into the basement and its most finished room, the room where he and others identified the door in the corner of the 1944 Christmas Day photo. He put us in front of the very wall that our father stood during the war. Chilled by this, the photo’s story suddenly had a sequel.

This former bomb shelter now vibrant classroom, had a table in its middle, with a white tablecloth, a few bottles of champagne, and hors d’oeuvres. This was not just an event or even a strange reunion. It was a commemorative ceremony. The regional press from Thionville arrived, as well as Ms. Frederique Munerol, the Communications Director for the City of Terville, who presented each of us with a handmade ceramic bowl on behalf of the Mayor of Terville. Finally, Ms. Bernadette Merz, formerly Bernadette Aime, and her granddaughter Karin, arrived. Mr Leleux formally introduced the Aime family to the Schwartz family, a reunion indeed, 73 and half years later. Everyone stepped back as Ms. Merz was presented with the photo. Her face brightened, as she identified her family: her sister Felie, age 10, her brother Adolph, age 17, sister Therese, age 22 and her mother, Madeline, age 46. Ms. Merz herself was 7 at that time but was 2 hours away with other family members, she returned to Terville in September 1945. As we talked through translation about the photo and that time of the war, she did not remember hearing about Christmas Day in 1944 and why her family was there in the basement. She then pulled out two photos of her family after the war, including her father and sister Odile, neither of whom were in the Christmas Day photo but all of whom survived the war. Champagne glasses were filled, all three of us stood before the very same wall of the photo, toasting the coming together of our families once again.

Ms. Merz went on to tell us the story of her family and their lives after the war. She is now 81 years old, was married in 1957 and raised 3 children in nearby Thionville. Her older sister Odile was living nearby, but unable to join us on this monumental day. The both of them are the only family members still alive. She then described, in amazing detail, the rest of her family and their lives after the war.

A journalist from the regional newspaper, Le Republican Lorraine, asked about our father’s life, his experience of the war, and his life after the war, including his years in Paris and Europe in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s. We remarked about his reluctance to talk about the war, and our current journey in his footsteps. Like a circle where a different artist begins and another completes it, a loop had been closed that we didn’t think was possible just hours before. We took photos in front of the school and said our goodbyes, aspiring to meet again. The next morning, our basement reunion was Le Republican Lorraine’s front page story.

More photos and footsteps to go

We left Terville for Bastogne, to the center of the Bulge to complete this phase of our journey. There are more photos in our father’s scrapbook, all from the post-war liberation and Allied occupation period. This first part of our journey in our father’s footsteps through the war has given us the opportunity to experience a component of an intangible aspect of our childhood upbringing: the impact the war had on our father, and subsequently on us. As we learned about and experienced these places of history and markers of time, some questions were answered but many more were generated. Why did our father go back to Paris so soon after Metz? Why was he assigned to assist a chaplain, where did they go and what did they do? Why was our father in Terville and what was he doing at the school on Christmas Day? What function did the Ecole Primare le Moulin serve for the US Army at that time? Where was he and who did he fight with during the Battle of the Bulge?

After our return home, Mr. Leleux discovered from the French archives that the governor of the Moselle region sponsored a Christmas tree project in each town of the area for the local children in 1944, the first Christmas since 1938 that France was free. His hypothesis is that our father, in his role as chaplain assistant and driver, was in Terville to support and perhaps participate in this project.

The 778th Tank Battalion’s journey across Europe, after having crossed the Rhine, twisted through southern Germany and stopped in Austria. Our father’s notes mark several of his experiences along the way, and his scrapbook includes photos of Nazi atrocities. After the war ended, he stayed in Europe until March 1946, having spent time in Czechoslovakia, Germany and Austria. With the scrapbook photos, map and Vest Pocket History of the 778th Tank Battalion as our guide, we hope to complete the journey of our father’s path through the war to Ulrichsberg, Austria, where the war for him ended and the occupation began.

As Rick Atkinson said in “The Guns at Last Light,” World War II Europe was over at the signing in Reims on May 7, 1945, but it was not finished. The war in Europe finished the next day, on May 8, at a second signing ceremony led by the Russians in Berlin. We believe our father never set foot in Berlin, the headquarters of the catastrophic delusion that drove this war, but because this is where it was finally finished on May 8, 1945, it is where we hope to finish as well.