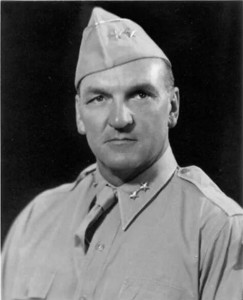

My father, Richard Van Arsdale, Sr., LTC, joined the Army at age 18. He was in the 75th Infantry Division, 289th Regiment. Dad and the 75th Infantry Division were activated on April 15, 1943, deployed to England in November 1944, and France in December 1944 to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The 75th Inf. spent 94 consecutive days in contact with the enemy. They went on to fight other battles.

My father, Richard Van Arsdale, Sr., LTC, joined the Army at age 18. He was in the 75th Infantry Division, 289th Regiment. Dad and the 75th Infantry Division were activated on April 15, 1943, deployed to England in November 1944, and France in December 1944 to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The 75th Inf. spent 94 consecutive days in contact with the enemy. They went on to fight other battles.

Like many of the men who fought in combat, my father did not speak much about his experiences during World War II. He fought in the Battle of the Bulge, Ardennes, Colmar Pocket and Ruhr Battles. He was awarded the British Star, Silver Star, Bronze Star w/ OLC, Purple Heart w/OLC and many other ribbons. We always wondered what lead to Dad receiving decoration of these medals, more than just knowing they were for “bravery in the field.” He never was one to boast, nor keen to hear others “blow their horn” either. Dad was very proud of his military service and all those who served. He would check in on his army buddies, and talk of the army reunions that both he and Mom loved to attend.

Sadly, my amazing Father passed away February 20, 2015. Dad’s home office was his domain and we did not disturb him there, much less ever inquire about what was in his desk. But it was a stroke of good fortune when I found many World War II mementos and letters in the bottom of his desk drawers. Citations received and written accounts of World War II battles struck me the most. Letters written to Mom and from his battlefield buddies told some of his stories of The Big One.

Corporal Van Arsdale was instructed to take a four-man daylight reconnaissance patrol into the town of LeBatty to ascertain the strength and disposition of enemy troops. Cpl. Van Arsdale and his patrol worked their way into the outer edges of the town, where they were ambushed by a large enemy patrol who demanded that they surrender. Defying them, this courageous corporal opened fire on the patrol, killing the two lead men. The enemy patrol then attempted to withdraw, but Cpl. Van Arsdale succeeded in taking one prisoner before he could escape. At this time, he signaled his getaway man to return with the information they had gained to the command post. Simultaneously, his two remaining men were killed by snipers. Then his prisoner attempted to escape, and Cpl. Van Arsdale killed him with one shot. Making his way back toward his company lines, he encountered an enemy machine gun nest. He attacked this strong point, killed the gunner, and then returned to his platoon. The following day he returned to the same area as a guide. “His knowledge of the positions occupied by the enemy were instrumental in the accomplishment of the objective,” read the Citation. The Silver Star, the third highest military decoration for valor and gallantry in action, was awarded Cpl. Van Arsdale for this mission.

In Germany, Dad was at the head of a series of patrols on dangerous missions. “Sgt. Van Arsdale repeated crossings of the Maas and Rhine Rivers and two patrols in one night across the Dortmund Ems Canal were accomplished with marked success. When an enemy machine gun threatened the safety of one patrol, Sgt. Van Arsdale distracted the enemy attention by throwing hand grenades at great risk to his own life enabling the patrol to complete its mission,” another Citation read. Dad wrote in a letter to Mom, “The Rhine is several hundred yards wide and the current is terrifically swift. We took off about nine o’clock that night, just when it was getting really dark. We had a little rubber boat that looked like a doughnut that barely fit the three of us. By the time we hit the other side we had drifted five hundred yards downstream. Three men isn’t a very big force to be going into the German lines, but we figured three of us could move faster and more quietly than a larger number of men. A much larger group of men tried to cross the night before in a bigger boat and the Krauts were waiting for them, and it didn’t end well. We had to be very quiet when we hit the shore, as it was covered with gravel. We had to take off our shoes and cross it in our stocking feet. It took about six hours to cover two hundred yards. We heard plenty that night—Heinies all over the place. We made it back to our side in the pitch black night and were almost shot by our own men.” The information they came back with allowed their platoon to successfully complete the mission. For his aggressive leadership and great courage, Sgt. Van Arsdale received the Bronze Star Medal w/ OLC.

Dad and his company were in Belgium advancing, when the Germans ambushed and attacked with sudden tree bursts. His buddy, Charlie Munder, was wounded so badly he couldn’t walk—shot in the left arm, his jugular vein severed, and with 3 fractures of his spinal column. Dad picked up Charlie and carried him back to get medical help. A letter from Charlie described the harrowing ordeal. He wrote, “Thanks for being so gentle with me, it saved my life!” Dad received two Purple Heart Medals for battle wounds received in action.

While he was a Staff Sargent, the company occupied a German area for six weeks and Dad was befriended by an old German couple. In La Fosse, Belgium, Dad and a few soldiers occupied the Julienne Family House. Dad later spoke about how kind they were and continued to correspond with the Juliennes, and visited them with Mom after the war.

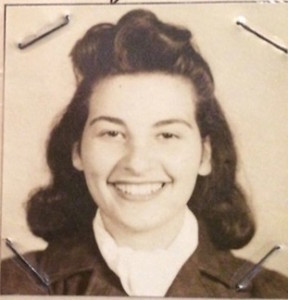

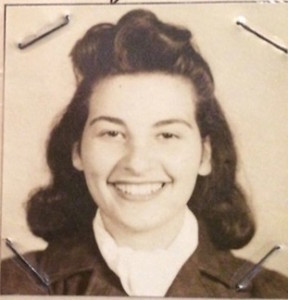

Our mother, Vera, worked building spy aircraft in Defense Effort at TailorCraft while Dad was fighting overseas. She was one of the Rosies who learned to fly, then soloed and became a pilot. To see pictures of her with the crew and her Civil Aeronautics registration is amazing.

Our mother, Vera, worked building spy aircraft in Defense Effort at TailorCraft while Dad was fighting overseas. She was one of the Rosies who learned to fly, then soloed and became a pilot. To see pictures of her with the crew and her Civil Aeronautics registration is amazing.

Dad returned from Europe on the SS Wheaton Victory in September 1945. He was aboard the Victory for 11 days. After serving in World War II, he served in the Korea Conflict, and in the National Guard where he was Commander of Heavy Mortar Company at Camp Cook, CA. Richard retired as a Lieutenant Colonel. “Dick” and Vera were married 70 years. Vera passed away on November 10, 2014 and Richard died only three months later. They were truly amazing parents—our heroes, who we remember, and miss, every day.

As his daughter, I wanted to share this information and say how proud I am of my Dad and Mom and all of you who have served. You are rightly named the Greatest Generation. I am grateful and give thanks to all men and women who served and continue serve our country. God Bless You.

by Laura M. Van Arsdale-Jacobson, Associate

Respectfully,

Respectfully,

My father, Richard Van Arsdale, Sr., LTC, joined the Army at age 18. He was in the 75th Infantry Division, 289th Regiment. Dad and the 75th Infantry Division were activated on April 15, 1943, deployed to England in November 1944, and France in December 1944 to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The 75th Inf. spent 94 consecutive days in contact with the enemy. They went on to fight other battles.

My father, Richard Van Arsdale, Sr., LTC, joined the Army at age 18. He was in the 75th Infantry Division, 289th Regiment. Dad and the 75th Infantry Division were activated on April 15, 1943, deployed to England in November 1944, and France in December 1944 to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. The 75th Inf. spent 94 consecutive days in contact with the enemy. They went on to fight other battles. Our mother, Vera, worked building spy aircraft in Defense Effort at TailorCraft while Dad was fighting overseas. She was one of the Rosies who learned to fly, then soloed and became a pilot. To see pictures of her with the crew and her Civil Aeronautics registration is amazing.

Our mother, Vera, worked building spy aircraft in Defense Effort at TailorCraft while Dad was fighting overseas. She was one of the Rosies who learned to fly, then soloed and became a pilot. To see pictures of her with the crew and her Civil Aeronautics registration is amazing.

Our chapter has a beautiful monument in the el Presidio Park in downtown Tucson, where we have patriotic celebrations and wreath laying ceremonies. We also continue to participate in the community to include school presentations, media interviews and activities with local veterans groups and fraternal organizations.

Our chapter has a beautiful monument in the el Presidio Park in downtown Tucson, where we have patriotic celebrations and wreath laying ceremonies. We also continue to participate in the community to include school presentations, media interviews and activities with local veterans groups and fraternal organizations.