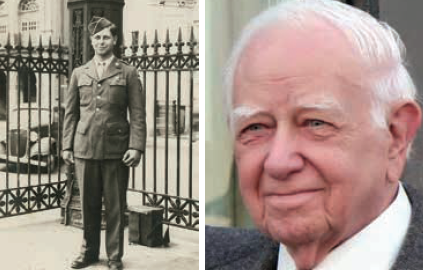

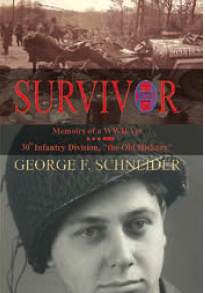

BOBA veteran member George Schneider passed last year, and his daughter Barbara-Ann shared his book, SURVIVOR: Memoirs of a WWII Vet, 30th Infantry “The Old Hickory.” The following is an excerpt regarding his unit’s involvement in the Battle of the Bulge and what they discovered in Malmédy:

By now, the weather was horrible even though the sky was clear. Snow was ankle to knee deep, and temperatures were well below freezing. We were now getting many casualties from frozen feet. We were poorly equipped with only our leather combat boots and thin socks. One of our generals rounded up all of the GI blankets he could find and sent them back to the Netherlands or Belgium where he had local women make booties from the blankets. We wore them inside a pair of overshoes and managed to keep our feet from freezing as we plodded on to the south.

Sometime around December 19th or 20th, we began to hear rumors of a massacre of Americans near Malmédy. Information was sketchy, but the word was spreading that the number of those slaughtered was significant, and most alarmingly, the Germans were not taking prisoners.

On the outskirts of Malmédy, we reached a small community called Géromont. There were only a few houses along the main road, and in these houses, our company established our headquarters for a couple of days.

One more mile south of Géromont, a distance of approximately 2 miles from Malmédy, we came to the intersection of five country roads which we named Five Points. Not more than two or three houses were in this area. There were no signs to indicate that the community had a name, and our maps didn’t identify the village, but today it is called Baugnez, and this small piece of geography is now well known to military historians as the site of the Malmédy Massacre.

The frigid winter air shrouded this site. We were now witnessing the site of the worst massacre of American troops by the Germans in WWII. In the snow-covered field adjacent to Five Points lay 86 frozen bodies, the only evidence of the atrocity manifested by humps in the snow and occasional exposed body parts and clothing. Each mound was a soldier. A man. Although I knew none of these men from the 285th, I felt a bonding with these fallen comrades, and we all felt a renewed hatred for the SS and elevated our resolve to pay back the perpetrators. The massacre had taken place during the initial German attack on December 16, 1944 when elements of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion were captured on December 17th. More than one hundred men were herded into the open field near the intersection of five points and machine gunned in cold blood. It was not until our drive south of Malmédy on this day, January 14, 1945, that the massacre was confirmed when units of my 120th Regiment discovered the frozen, snow-shrouded bodies. Some survivors of the massacre had reported the tragic encounter with the advancing SS troops, but the reality was confirmed by us twenty-eight days after the massacre.

While I viewed this tragic scene, just a few yards away, a jeep load of media correspondents drove up and parked in the intersection of Five Points to document the massacre. We knew the Germans had an 88 zeroed in on the intersection, so we stayed clear of this target. I was close enough to observe a shoulder patch on one of the neatly dressed reporters that identified him as being from Brazil. Reporting of the massacre had apparently made news throughout the world. Shortly after the reporters dismounted the jeep, an 88 narrowly missed the jeep and exploded a few yards away. The artillery piece was probably along the road to Ligneville, our next objective. One round was all the reporters needed to hasten a retreat to Malmédy without any photographs for their archives.

I, along with my 30th Division, left the bodies as found, and the Graves Registration Battalion later identified the bodies and removed them from the field. Baugnez, a.k.a. Five Points, will always be remembered as the site of the infamous “Malmédy Massacre”.

Although it was initially reported that as many as 135 men had been executed, the final count now stands at 86. Most of the 86 were members of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. Many Americans living today claim to be survivors, but few truly are. I can vouch for two survivors, Robert “Sketch” Mearig and Harold Billow. Into the new millennium, both were still active members of our local chapter of the Veterans of the Battle of the Bulge, the South Central, PA Chapter. The following depicts the events of the massacre as told to me by my friends Harold and Sketch:

It is late afternoon and quickly getting dark. The Germans herd the Americans into an open field where an SS officer surveys his catch with pride. Suddenly he shoots the guy standing next to Harold in the head.

Then he shoots the guy on the other side. He shouts a command to the machine-gunners, and they open up. Sketch & Harold, although not yet hit, drop to the ground and play dead amongst the corpses of their buddies. After all the men have fallen, the officer calls a halt to the firing and inspects his trophies. Sketch & Harold stifle their breaths as they listen to the officer walking amidst the bodies, checking for signs of life. The SS officer, speaking perfect English, would ask if anyone was wounded, and if he gets a positive response, he has a target. He asks one soldier if he is wounded, and getting a moan in response, he shoots the soldier in the head. The officer continues his walk among the pile of bodies, and any movement or groan is terminated with a shot to the head. He kicks them in hopes of getting a reflexive response. When he comes across Harold, he kicks his boot. Harold doesn’t flinch. The officer moves on, arbitrarily choosing bodies to kick. A few flinch or moan. He shoots them. Now satisfied that they are all dead, he orders his men to move out. By this time, it is fairly dark, and with just a handful of Germans now still at the site, Sketch decides to make a break for it. He is near the far end of the field and believes he has a shot at it. He flees toward the woods and, while under fire, disappears. Harold and another guy decide to make their break. They dash towards a house on the corner and make their way inside. Realizing the Germans had probably seen them go in and would probably come after them, they race out the back door and high tail it toward Malmédy. Sketch spent three days wandering in the woods between Baugnez and Malmédy before finally being rescued by our regiment. Regimental Commander Col. Purdue took him back to his quarters and gave him his bed for the night.

In Summer 2020, the 30th Division was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for their critical victory during the initial months of the Normandy invasion and extraordinary heroism at the Battle of Mortain, France, in 1944. George’s daughter wrote, “My dad passed having only one unresolved issue in his life—to see the Old Hickory finally awarded this citation. He contacted several people close to the president, but he did not live long enough to see it actually happen… I know this award means the world to all Old Hickory survivors.

If you’d like a copy of George’s book, his daughter Barbara-Ann is offering it “at cost” to BOBA members ($19 total with shipping for US only) which is less than the Amazon rate. To order, contact her at vbobgeorge@gmail.com.