Georgia Military Veterans Hall of Fame

Searching for Bill Lewandowski

(from Diekirch/Luxembourg)

My name is Daniel JORDAO and I am from the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg. I’m currently assisting the Dudzinski family to locate former GIs who were billeted in their house in Diekirch in late November 1944.

One of those GIs’ name was Bill (William?) Lewandowski with Polish origins. There were also other Polish-descending soldiers billeted in Diekirch in late November 1944. Four of them, attended the wedding of the Dudzinski-Weber family on November 25th, 1944.

The exact outfit of Bill Lewandowski and his fellow Polish-descending GI friends is not known. According to official documents dating back to that time, I assume that they were members of the 28th Infantry Division – and most likely 109th Infantry Regiment – 3rd Battalion. As most of the men of the 28th Infantry Division were from Pennsylvania and Delaware, there might be a chance that Bill Lewandowski and his fellows came from one of these states.

Bill Lewandowski had a picture taken at a local photographer shop in Diekirch where you can see that he wears a wedding ring, so that I hope that might still be relatives living. The Dudzinski family was told that Bill did not survive the Battle of the Bulge and that he was KIA in Luxembourg, probably in December 1944 (not confirmed, though!).

Mrs Annie Dudzinski-Weber is now 90 years old and would like to find out more about Bill and the other GIs who attended her wedding.

Can anybody help in this research? Does anyone recognize one of the GIs on the wedding picture or knows a relative of Bill Lewandowski? Any help is welcome.

Please write to:

National Museum of Military History

c/o Daniel Jordao

10, Bamertal

L-9209 Diekirch

Luxembourg / Europe

Or email to:

dcj@jordao.lu

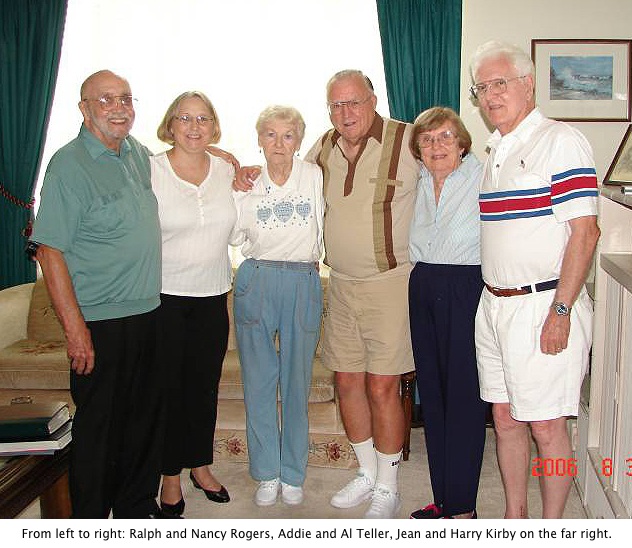

104th Vets together again

I was contacted last week by a guy I went through the war with and haven’t seen in the 61 years since. His son, who works in Washington, found my name in the course of some of his research and recognized the104th Inf. as being his Dad’s outfit. He checked with his father, who said he knew me, and mailed him the info. It included the fact I was President of the VBOB Chapter in Eustis, FL. so he addressed a letter to that location.

I haven’t missed a VBOB meeting in five years, until our Aug meeting, due to having two teeth extracted the day before. Our treasurer phoned me after the meeting and told me I had a letter there (at the VFW Post) from a “Ralph Rogers.” My old army buddy is the only one I know with that name. I told him to read it to me. It began: “You have got to be the Harry Kirby I served with.” I immediately phoned Ralph and we wasted no time arranging a meeting.

I phoned another of our guys who lives in the area, Al Teller, and invited him to a reunion lunch today at my house in Ocala,FL. We all played in the 104th Infantry Regimental Band, 26th Infantry (“Yankee”) Division. I know the TOO doesn’t provide for a Regimental Band . . . but we had one (CP Security in combat)! Al Teller was the band director, I played a trumpet and Rogers was our bass drummer.

Needless to say it was a great time, and I think our wives enjoyed it as much as we did. So over chicken crepes and wine, we shared photos and rehashed old times for about three hours. There will be more get togethers now that we have made contact.

Harry Kirby

Source: The “Yankee” Division in World War II

I was contacted last week by a guy I went through the war with and haven’t seen in the 61 years since. His son, who works in Washington, found my name in the course of some of his research and recognized the104th Inf. as being his Dad’s outfit. He checked with his father, who said he knew me, and mailed him the info. It included the fact I was President of the VBOB Chapter in Eustis, FL. so he addressed a letter to that location.

I haven’t missed a VBOB meeting in five years, until our Aug meeting, due to having two teeth extracted the day before. Our treasurer phoned me after the meeting and told me I had a letter there (at the VFW Post) from a “Ralph Rogers.” My old army buddy is the only one I know with that name. I told him to read it to me. It began: “You have got to be the Harry Kirby I served with.” I immediately phoned Ralph and we wasted no time arranging a meeting.

I phoned another of our guys who lives in the area, Al Teller, and invited him to a reunion lunch today at my house in Ocala,FL. We all played in the 104th Infantry Regimental Band, 26th Infantry (“Yankee”) Division. I know the TOO doesn’t provide for a Regimental Band . . . but we had one (CP Security in combat)! Al Teller was the band director, I played a trumpet and Rogers was our bass drummer.

Needless to say it was a great time, and I think our wives enjoyed it as much as we did. So over chicken crepes and wine, we shared photos and rehashed old times for about three hours. There will be more get togethers now that we have made contact.

submitted by Harry Kirby

Source: The “Yankee” Division in World War II

On October 11, 2014 my father, Harvey S. Meltzer, then living at the Asbury Methodist Village in Gaithersburg, MD, with his wife Phyllis, and feeling just fine, went to take a nap in the afternoon so he would have energy for dinner out that night. He never woke up. He was 88 years old, and died as peacefully as a man could. His life was less peaceful, and his experience with the 90th Division, and in the Battle of the Bulge, went to form the core of his life in so many ways.

It started when he turned 18 and went to opt for accelerated induction in the town he grew up in, Worcester, MA. He was told there wasn’t anyone listed under the name of Harvey Meltzer and when he went home to ask his parents what was going on, he was told by them that his real birth name was Seymour Harvey Meltzer, not Harvey S. Meltzer. A neighbor had teased him as a child, so his parents decided to switch his 2 names, forgetting to tell him! Despite that shock, he nevertheless got to register, and kept his Harvey S. Meltzer name for the rest of his life.

Ultimately, he was assigned to the 42nd infantry division until the night he had his memorable Christmas 1944 dinner in Strasbourg. Until that moment he had never been close to combat. But back in camp after dinner that night, his outfit was ordered to wake up and told to board trucks, in which they were driven all night, and then told to get off the trucks. Not much else was told them (sound familiar to you fellow infantrymen?). As it turned out he was at that moment being transferred to the 90th Division in Patton’s 3rd Army and headed north into the Battle of the Bulge. He was part of the 359th Regiment, Company F.

His first experience of combat that he remembers was that his new outfit was ordered into the woods in Luxemburg to relieve the 26th Yankee Division (he believed), who had to that date been unable to dislodge the Germans from a key point in that sector. His first taste of combat was a night attack into those woods. He remembered little of that night, other than the tracers and noise and neberlwerfer shells and death and shooting- all as an 18 year old.

He survived, made it through the Battle of the Bulge, was awarded a purple heart after being hospitalized twice for frostbite of both his feet, and survived the rest of the war, helping liberate the concentration camp Flossenburg, in Czechoslovakia, in the process.

For many years after the war, he awoke every night with screams and cries and nightmares, but refused to talk about it. He also refused to visit or return to Europe until middle age, because he could not face his nightmares there.

But, his wartime experience gave him the opportunity to go to college under the GI bill (his family was not well off), and with his accounting degree he ultimately had a very successful career as head of royalties at Columbia Records, part of CBS. He was married many years to my mother, Pauline, and then many further years to my stepmother Elena, and after she passed away, he again found happiness in his 80s and married his surviving wife, Phyllis. But during the prime of his life though, he carried all his experiences and memories inside himself, sharing them with very few people.

Then VBOB came along and he went to one of the VBOB reunions in Europe- I believe the 40th, and it transformed him. All of a sudden, he became aware that he was not alone anymore- he met so many other veterans who “understood” and who shared his pride and his pain. And he fell in love with Europe and vacationed there often, after.

He attended the 50th VBOB anniversary too, and I had the honor of taking my father to the 60th Anniversary, where we had one of the best weeks of our lives together. I got to meet so many wonderful veterans, and I got to see the battlegrounds and meet the people of Belgium and Luxemburg, who treated all the veterans as if they were liberators that very week- it was wonderful.

I also got to discover, first hand, where my dad’s first night of combat occurred- it is now a national park in Luxemburg- Shumann’s Eke. My dad’s outfit, and others, DID push the Germans out, and that was the start of their withdrawal out of Berle, Luxemburg. He was honored there during our trip, as were others, at the monument located outside the famous woods and by the people of Berle, who carried the torch of memory and thankfulness into our present..

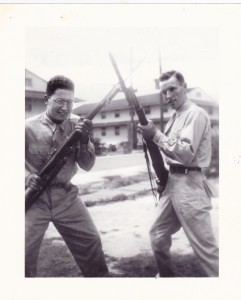

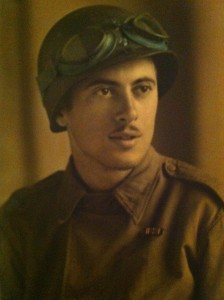

My dad has, ever since VBOB, gotten involved again with his 90th Division Association reunions too, and his group therapy sessions at the NYC VA (PTSD). Indeed, his rolodex, upon his death, had more veterans names in it, then anyone else. My Dad is survived by his wife Phyllis, me and my wife (his daughter-in-law) Wen Xian, his grandsons Zachary and Benjamin, his daughter Sandra and son-in-law Jeff, and his granddaughter Elizabeth, and many friends and family who loved him. I am attaching 2 pictures of my dad- as a young soldier, and as a very proud older veteran.

I am his son Curt Meltzer, and I wanted to write this Remembrance to Honor my father, and his service during WWII. Thank you all for showing my dad he was not alone- thank you all for your friendship and caring and understanding, and for the Honor to yourselves and our Country that you all have brought with your service. God bless you.

Curt Meltzer

Edward “Babe” Heffron and William “Wild Bill” Guarnere — two World War II heroes from South Philly immortalized in the book and miniseries Band of Brothers — will be honored with bronze statues somewhere in the city.

TO ALL THE KIDS WHO SURVIVED THE 1930s and 40s, the 50s, 60s and 70s!

First, we survived being born to mothers who took aspirin, ate blue cheese dressing, tuna from a can and didn’t get tested for diabetes. Some even smoked or might even have had an occasional drink while they were pregnant.

Then after that trauma, we were put to sleep on our tummies in baby cribs covered with bright colored lead-base paints.

We had no childproof lids on medicine bottles, locks on doors or cabinets, and when we rode our bikes, we had baseball caps, not helmets on our heads.

We didn’t even have clips to keep our pants legs out of the chain – we might even have been wearing knickers.

We wore no fancy, expensive sneakers – a pair of Keds was two bucks, and we were only allowed to wear them in gym.

Ladies, do you remember those ugly bloomer gym uniforms you wore in High School

As infants & children, we rode in cars with no car seats, booster seats, seat belts, no air bags, on bald tires and sometimes with brakes that didn’t work too well.

Oh, good Lord – there was no air-conditioning in the car! (Or anywhere else, for that matter.)

Riding in the back of a pick-up truck on a warm day was always a special treat.

We shared one soft drink with four friends from one bottle and no one actually died from this.

We ate cupcakes, white bread, real butter and bacon.

We drank Kool-Aid made with real white sugar, and, we weren’t overweight.

WHY? Because we were always outside playing…that’s why!

We could leave home in the morning and play all day, as long as we were back for meals and when the streetlights came on.

No one was able to reach us all day, and, we survived.

There were no school buses, in the city, at least, so we walked – through snow and rain or shine,

We could spend hours building our go-carts out of scraps and then ride them down the hill, only to find out we forgot the brakes. After running into the bushes a few times, we learned to solve that problem.

Anybody remember taking an orange crate, a piece of two by four and an old Chicago roller skate, and build on of those scooter things? We even rode those in the gutters without getting hit by a car!

We had no PlayStations, Nintendo’s or X-boxes. There were no video games, no 150 channels on cable, no video movies or DVD’s, no surround-sound or CD’s, no cell phones, no personal computers, no Internet and no chat rooms.

We had friends, and we went outside and played with them!

We fell out of trees, got cut, broke bones and teeth, and there were no lawsuits from these accidents.

We ate worms and mud pies made from dirt, and the worms did not live in us forever.

We were given BB guns for our 10th birthdays, made up games with sticks and tennis balls and, although we were assured it would happen, we did not put out very many eyes.

We rode bikes or walked to a friend’s house and knocked on the door or rang the bell, or just walked in and talked to them.

Little League had tryouts and not everyone made the team. Those who didn’t had to learn to deal with disappointment. Imagine that!

Hey, there was no Little League! We just found an empty field in the country or an empty lot in the city, chose up sides and played!

Any of you city-bred remember Ring-O-Levio, Johnny on a Pony, stick ball and the mean old lady who kept your ten cent pink ‘Spaldeen’ if it went into her front yard?

How about stoop ball? Chinese handball?

The idea of a parent bailing us out if we broke the law was unheard of. They actually sided with the law!

These were the generations that produced some of the best risk-takers, problem solvers and inventors ever. If YOU are one of them, CONGRATULATIONS!

The past 50 years have been an explosion of innovation and new ideas. We’ve had freedom, failure, success and responsibility, and we’ve learned how to deal with it all.

You might want to share this with others who have had the luck to grow up as kids before the lawyers and the government regulated so much of our lives for our own good. While you are at it, forward it to your kids so they will know how brave and lucky their parents were.

Kind of makes you want to run through the house with scissors, doesn’t it?

Submitted by the Duncan Trueman Chapter

The Bulge Bugle

PO Box 336

Blue Bell, PA19422

Enclosed is information from South Dakota State University about the passing of my friend Sherwood Berg. I don’t know if he was a member of VBOB, but noticed that he had been a pall bearer for General Patton so figured that might be worth a mention in The Bulge Bugle. He also had crossed the Ludendorf Bridge at Remagen with the 78th Infantry Division.

I was in a statistics class with him at South Dakota State after the war and marveled at his superior intelligence. As I recall there were only seven or eight of us in the class and I was clearly at the bottom. Until I read the enclosed material I had no idea that we were so close together during WWII. My 8th Armored Division crossed the Rhine at Wesel, just above Remagen ~ about ten days later. We had a vets club at South Dakota State and both of us were in it, but I don’t recall any of us talking about our war experiences. I guess we had had our fill of war.

Click on the link below to read Sherwood’s obituary

http://www.brookingsregister.com/v2_news_articles.php?heading=0&story_id=20100&page=80

Yours truly,

Vernon E Miller (130th Ordnance Battalion)

My father, Anthony John Capozzoli was 18 when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in February 1943, the fourth son to go in his family. He left his job at Temple Music in Rockville Center, Long Island, New York, and reported to Camp Upton, located in Suffolk County, Long Island, for a few days.

He travelled by train to Camp McCain, MS where he was assigned to Headquarters Company 346th Infantry Regiment for several weeks. “The barracks were made of packing crates with tar paper over them. There were 2 potbelly stoves you were assigned to maintain. It was the middle of winter down there,” he explained.

From there he went to Fort Bragg, NC for a few months. “We went out on maneuvers —learning how to fight—going under barbed wire with real machine guns firing over you—role playing as if you were in combat,” he told me. He had the job of cleaning the latrines while there, a job that kept him in a warm location.

This training was followed by a 6-month stint at Fort Benning, GA. where he attended school to learn Morse Code. “We would get up about 3 o’clock in the morning, have breakfast, then we went to an area where we sat at a table, put earphones on and practiced Morse Code. We had to read what you heard,” he said.

With training in communications as a radio operator, he went back to Fort Bragg to join the rest of his company. He, along with other members of the 87th Infantry Division, boarded the Queen Mary in October 1944 and travelled to Scotland on a 4-day voyage. They stayed in Scotland until their equipment arrived. He drove a big truck down to Dover, England with the rest of the convoy. “I had never driven a truck in my life,” he noted.

The 87th Infantry Division crossed the English Channel on a liberty ship and arrived in LeHavre, France, in November of 1944. As part of the 87th, he travelled through France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany mostly by Jeep. The mission was specific, where “whenever we got to a town, we would cut the lines of communication and set up our own.” He explained that: “We camped in houses when we took over a town” noting that “our communications people were behind the infantry.” They knew they were supporting the troops, but “we did not know what we were sending because it was in code. The message center would decode it after it arrived.”

Dad participated in campaigns in the Ardennes, the Rhineland, and in the Battle of the Bulge as part of Patton’s Third Army. During this battle, he assisted in keeping wire communications for the 346th HQ Company of the 87th Division. He recalls going as far as Yugoslavia before stopping so that the Russians could come in and occupy part of Germany. At this point, the war in Europe had finally ended.

He went back to Germany where they were assigned to a camp while waiting to sail home. Upon his return to the U.S., he was on furlough for 30 days during August 1945, awaiting assignment to fight the Japanese in the Pacific. But the war ended.

Because Anthony did not have enough points to be discharged, he was sent from Boston where their ship landed, to Sandy Hook, NJ, which was a reception center for new recruits. Here his job was handing out uniforms. Whenever possible, he went home on weekends by boat to Brooklyn and from there, by train back to Freeport, NY.

After his discharge, Anthony returned home to Freeport, resumed his job, and attended New York Radio Institute in New York City at night. He married Joan Michalicki in 1950. They settled in Merrick 5 years later. Until his retirement in 1989, he owned his own business as a television/radio technician. He moved to Sebastian, FL in 1991. This year he celebrated his 90th birthday there with family and friends.

After his discharge, Anthony returned home to Freeport, resumed his job, and attended New York Radio Institute in New York City at night. He married Joan Michalicki in 1950. They settled in Merrick 5 years later. Until his retirement in 1989, he owned his own business as a television/radio technician. He moved to Sebastian, FL in 1991. This year he celebrated his 90th birthday there with family and friends.

Submitted by Mary Jane Capozzoli-Ingui

The mission of the AVC is to guard the legacies and honor the sacrifices of all American veterans. Through oral history preservation, educational programs and civic events, we pass their stories on to the next generation so that they are never forgotten.

Click here to visit the AVC web site

Observance Veterans Day is intended to honor and thank all military personnel who served the United States in all wars, particularly living veterans. It is marked by parades and church services and in many places the American flag is hung at half mast. A period of silence lasting two minutes may be held at 11am. Some schools are closed on Veterans Day, while others do not close, but choose to mark the occasion with special assemblies or other activities.

Observance Veterans Day is intended to honor and thank all military personnel who served the United States in all wars, particularly living veterans. It is marked by parades and church services and in many places the American flag is hung at half mast. A period of silence lasting two minutes may be held at 11am. Some schools are closed on Veterans Day, while others do not close, but choose to mark the occasion with special assemblies or other activities.

Veterans Day is officially observed on November 11. However, if it falls on a weekday, many communities hold their celebrations on the weekend closest to this date. This is to enable more people to attend and participate in the events. Federal Government offices are closed on November 11. If Veterans Day falls on a Saturday, they are closed on Friday November 10. If Veterans Day falls on a Sunday, they are closed on Monday November 12. State and local governments, schools and non-governmental businesses are not required to close and may decide to remain open or closed. Public transit systems may follow a regular or holiday schedule.

History On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 an armistice between Germany and the Allied nations came into effect. On November 11, 1919, Armistice Day was commemorated for the first time. In 1919, President Wilson proclaimed the day should be “filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service and with gratitude for the victory”. There were plans for parades, public meetings and a brief suspension of business activities at 11am.

History On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 an armistice between Germany and the Allied nations came into effect. On November 11, 1919, Armistice Day was commemorated for the first time. In 1919, President Wilson proclaimed the day should be “filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service and with gratitude for the victory”. There were plans for parades, public meetings and a brief suspension of business activities at 11am.

In 1926, the United States Congress officially recognized the end of World War I and declared that the anniversary of the armistice should be commemorated with prayer and thanksgiving. The Congress also requested that the president should “issue a proclamation calling upon the officials to display the flag of the United States on all Government buildings on November 11 and inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches, or other suitable places, with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.”

Click here to read where celebrations will be held across our Country.