by Robert S. Scherer, 106 INFD ARTY HQ BTRY

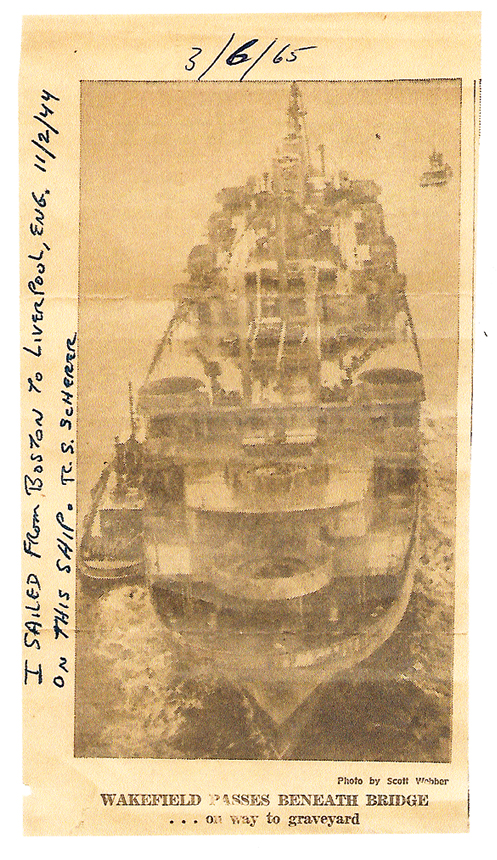

It’s about 7:15 AM on March 5, 1965 and my friend and I are sitting in slow-moving, toll bridge back-up traffic on the Tappan Zee Bridge over the Hudson River, on our way to work, in White Plains, New York. This morning is bright and clear. Today is my friend’s turn to drive and I’m trying to nap. Suddenly he says, “Hey, look at that big ship under us.” I look out the window and there it is, moving south towards New York City. It is being pushed by a tugboat lashed to the port side of the stern. As the ship clears the bridge I can see its name. It is called “Wakefield.” I repeat the name to myself—it seems familiar. Then I remember: that’s the name of the ship that took me from Boston to Liverpool, England in 1944. I tell my friend and explain the circumstances to him. Traffic has now moved on and we are out of sight of the ship.

The next morning he gives me a newspaper clipping, from the Nyack News Journal with a picture of the ship and the title “Old Troopship Fades Away Into The Night.”

Evidently, the ship had been in the Maritime Administration’s Hudson River Reserve Fleet at Jones Point, New York just south of the Bear Mountain Bridge. This is where they stored old liberty ships until they are sold for scrap. Now it was on its way to the scrap yard In Kearney N. J.

The last sentence in the clipping reads, “Who knows but what some of those commuters once rode on her proud decks?’ I jotted down: “I DID.” Here’s my experience aboard the Wakefield:

The 106 Infantry Division was commissioned on March 15, 1943, at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. We trained while the Army took over 7000 troops as replacements for divisions in combat. After maneuvers in March 1944, the division moved to Camp Atterbury outside Indianapolis Indiana. Still more training of replacements.

Then, in early October, the division prepared for an overseas assignment. More training and arms qualification. On or about November 1, 1944 the division traveled by train to embarkation ports. The infantry went to a camp near New York City. The artillery went to Camp Myles Standish just outside Boston, MA. We spent two weeks waiting for our ship. Then, about November 18, we boarded the Wakefield. The headquarters battery was assigned to compartment 0 – 2, which was on the bottom deck and in the bow of the ship.

Shortly after arriving in our quarters, a sergeant announced that he needed volunteers for jobs while onboard ship. First, he asked for volunteers to be messengers. I immediately raised my hand. Secondly, he asked for volunteers to man brooms and cleaning equipment. I don’t remember how many hands went up for that!

Being a messenger meant taking messages from the radio room to various places on the ship. So, the next morning when we sailed, I reported to the radio room for duty along with three or four others. Messengers wore a white armband which allowed them access to various parts of the ship. For example, being able to go to the head of the mess line. I spent the morning delivering messages to various officers on the A deck and the afternoon sitting on the floor of the passageway playing cards.

Every morning an announcement came over the ship’s loudspeakers: “Now hear this, Army sweepers: man your brooms, clean sweep fore and aft!” The message was repeated twice more.

The mess hall was on the B deck, in the center of the ship. It was filled with rows of long tray tables from side to side. These tables were stainless steel with a 3 inch rim, on either of the long sides. The ends had no rim and when the ship rolled, the food trays would slide in that direction. The trays at each end would fall off. You soon learned to hang onto your tray.

The third day was very stormy. The ship was headed into the waves, so it would climb to the top of a wave and then crash to the bottom and so on, as well as roll from side to side. While waiting outside of the radio room, I noticed a door at the end of the passageway and walked over to see outside. But, because there were no windows in the door, I opened it and stepped outside to a platform. I watched as the waves rose and fell before the ship. I hung on to the railing tightly and looked up as we hit the bottom of the trough, and believe me, that wave was at least 40 feet high! I quickly went inside.

On the fourth day of the crossing, in calm seas, I could see we had picked up an escort of destroyer escort vessels. That meant we were nearing our destination. On the fifth day we arrived at the port at Liverpool England and disembarked to travel by train to a camp somewhere in the middle of England. Two weeks later we again boarded a vessel, for another sea voyage—this time an LST to cross the channel.

We sat outside Le Havre for two days and finally the General raised his one star flag. We finally docked about 6:30 PM that evening. The rest is history.

Seventy three years later, I still remember it as though it happened last month.