This is a selected excerpt about US Army soldier Charlie Sanderson from My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers, a book of first-hand narratives and photos chronicled by BOBA Member Charley Valera.

Unlike most soldiers who finished their training and were selected to be shipped overseas, [Charlie] Sanderson was rushed over as a replacement and completed his basic training in Salisbury Plains, England, near the white cliffs of Dover—not a pleasant or safe place to be in early 1944.

Sanderson was now official property of the US First Army, 552nd Field Artillery Battalion, 78th Infantry Division, AAA Automatic Weapons Battalion under Major General Edwin P. Parker. Sanderson soon found himself landing on Omaha Beach and would eventually end up in the Ardennes Forest.

Moving forward into Normandy and other parts of France, the troops fired on the towns of Saint-Lô and Sainte-Mère-Église. “Return fire was nonstop. Everything was coming at us.

One time, I looked up over the hill and saw all the tanks lined up,” Sanderson said. “I thought they were American tanks. They were Germans and they started firing at us. We were laying out a position and didn’t know we had gone too far.” The land between the two fighting sides is known as no-man’s-land. Sanderson’s troop had gone too far into German-occupied territory; they had to get out of there in a hurry.

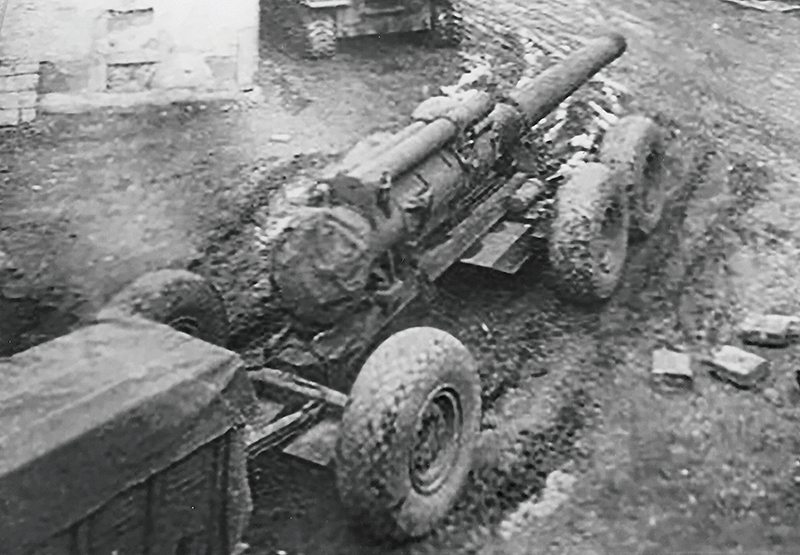

Again, Sanderson was part of the 552nd Field Artillery Battalion. They had three gun batteries: A, B, and C Battery. Their weapon was the enormous, American-made 240 mm Howitzer Cannon that would shoot a 365-pound projectile within a twenty-mile range, using eighty-five pounds of gunpowder per shot. This big weapon of war could also be moved around as needed to advance.

Once a position was established and laid out, Sanderson began to empty his truck for action. He took a big canvas and put it down exactly where the massive Howitzer gun was to be located. The canvas had holes in it with metal grommets, and it took three men to lay it out. Assigned to a twenty-one-man crew, Sanderson was up front first. They’d put the large steel spades attached to the sides of the gun into the ground for support, but needed large enough holes to accommodate the recoil based on the gun’s nose’s aim. When the other part of his crew showed up, all they had to do was start digging. After that, they placed “a thousand sandbags around it,” Sanderson said. “Sometimes you had soft or sandy soil to work with.”

They used prime movers to move the Howitzers around—not a tank. A prime mover is a specialized heavy-duty gun tractor used to tow artillery pieces of various weight and sizes. They took two prime movers and put them at 45 degrees on either side of the Howitzer, cabling the gun to them for further stability.

Each man had his own job. A gunner would sit on a metal seat on one side of the gun and did quadrant lateral settings. Another sat on the other side, configuring the elevation settings. The two spun the big steering wheels for accuracy. When ready, the gunner got on a phone with the commander and yelled, “Set,” then “Ready” and the commander on the other end of the line would tell them when to fire. To work just the gun, “There would be two men on the gun; seven on ram-staff and four to bring the projectile out.”

With seven men on the ram-staff, a twelve-foot manual push rod got the projectile into the gun. “They’d yell, “One, two, three … ram!’ and slam the 365-pound bullet into the barrel of the Howitzer. It all went as fast as you could go … to have a round in the air every minute.”

There was a sergeant in charge of maintenance for all this equipment. The prime movers were all covered in camouflage to hide from reconnaissance planes. “The noise was tough,” explained Sanderson. “You were supposed to stand on your toes, open your mouth, and block your ears. How you gonna do that when you had to measure the recoil on the gun? The gun would recoil sixty-five inches,” he remembered. “The hotter the gun got from firing, the farther back the gun would recoil.”

“We needed cooks, truck drivers, mechanics, and others soldiers’ efforts of the unit to make it all work. Some of the others would be guarding the trucks and facilities during the shooting. You had guard duty, two “on and four off, and sometimes we’d agree to four on and two off to give more people a break or [to] sleep more at night. But you had to be close to your gun. Your pup tent was very close by the gun. When they called a fire mission, you had to be quickly available. Or, if there was a fire mission and you were sleeping … well, at least trying to sleep during all of that.”

Further inquiry about his crew continued. “The sergeant is like the head mechanic; he knows what’s to happen and when to move on. Everything is camouflaged and ready to go when needed. They all carried the carbine rifles with a sling over their shoulders.” He shook his head. “Nobody could believe what it was like.”

In front of the guns was a six-foot pile of loose grass or dirt caused by a vacuum from the firing. “One time, “on and four off, and sometimes we’d agree to four on and two off to give more people a break or [to] sleep more at night. But you had to be close to your gun. Your pup tent was very close by the gun. When they called a fire mission, you had to be quickly available. Or, if there was a fire mission and you were sleeping … well, at least trying to sleep during all of that.”

Further inquiry about his crew continued. “The sergeant is like the head mechanic; he knows what’s to happen and when to move on. Everything is camouflaged and ready to go when needed. They all carried the carbine rifles with a sling over their shoulders.” He shook his head. “Nobody could believe what it was like.”

In front of the guns was a six-foot pile of loose grass or dirt caused by a vacuum from the firing. “One time,” Sanderson recalled with a smile, “there was a half dozen sheep close by. We fired over them and there was a whole pile of loose wool in front of the gun. It didn’t pull it out of them, but loose wool from their bodies was in with the grass. It was kind of funny.”

The food was mostly K rations. The only time their cook was able to provide decent meals was when they got into a quiet zone where they could kind of lie back, with not much going on. They sometimes took the big kettles, which looked like metal garbage cans, and set four of them out. They then took extra gunpowder bags and threw them onto a fire—which got the water boiling in just a couple of minutes. They threw C rations into the water so they could have hot food. But most of the time, it was K rations. The benefits of K rations were for quick eating meals and maximum energy while C rations were more for sustained daily food intake.

K rations were individual portions of canned combat food and provided breakfast, lunch, and supper. According to Wikipedia, a day’s menu consisted of the following:

Breakfast Unit: canned entree (chopped ham and eggs, veal loaf), biscuits, a dried fruit bar or cereal bar, Halazone water purification tablets, a four-pack of cigarettes, chewing gum, instant coffee, and sugar (granulated, cubed, or compressed).

Dinner Unit: canned entree (processed cheese, ham, or ham and cheese), biscuits, fifteen malted-milk tablets (in early versions) or five caramels (in later versions), sugar (granulated, cubed, or compressed), a salt packet, a four-pack of cigarettes and a box of matches, chewing gum.

Sanderson shared some of his memories of the Battle of the Bulge: “During the Battle of the Bulge, the Germans spearheaded around us. We were in the middle, and they had us surrounded. The lieutenant told us, ‘We’re going to fight until the last man. The first man to turn around, I’ll shoot him in the back.’ That’s what the lieutenant told us. Blood and Guts, General Patton, came in with his tanks. When he came by, you could see those tanks rolling around. He saved our ass, you know. We were surrounded.” When asked if he’d ever met General Patton, Sanderson responded with a smile. “I drove past him once. I knew who he was, but he didn’t know who I was.”

From a distant memory, Sanderson remembered another interesting story, detailing what the Ardennes Forest looked like. “Did you ever see land when a tornado’s come through? Did you ever see trees and stuff, twisted and broken off? The whole friggin’ forest was like that. I drove down a road and there were horses hooked to cannons—German horse-drawn artillery. Our men came down through and strafed them. We just had to push them off the road so we could get through. Imagine that—using horse-drawn artillery in World War II. Everything the Germans had, they used. That was the Ardennes Forest.” Sanderson was stunned to see the once-mighty Third Reich reduced to using horse-drawn artillery.

“They called them battles, but to me it was a battle all the way through.”

Sanderson got plenty of special detail. They took him and his assistant driver to a huge field at night so they could run a wire for their phones. “A jeep would drive the wire across the field. They’d say, ‘Here, this is your position.’ It was right next to a row of turnips. The Germans planted huge rows of them. A row of turnips covered in brush used to feed their animals and troops. We were out there to report if they [the German troops] came in by parachute. We were sitting ducks out there in the middle of the friggin’ field. All by ourselves, you know. These kind of details, you don’t mind when you’re back with your men. But when you’re all by yourself, those kinds of detail kind of get scary.”

Sanderson added, “They’d come by and drop those personnel bombs. They’d drop them all over the place and they’d go pop, pop, pop all over the friggin’ place like popcorn. They also dropped flares so they could see. They’d see us sitting ducks next to the pile of turnips camouflaged like it was something else. I was probably nineteen years old.”

“When you can’t see it, you get scared. You don’t know where it’s coming from. Anyone who said they weren’t scared is a damn liar.”

The war had been over for more than seventy years when Charlie and I spoke about his life. The memory of his war efforts is etched in his mind as though they had happened yesterday—just like the others I’ve interviewed, they all seem to remember the war in great details. There was lots of smoke, fire, guns going off, aircraft strafing; it was war, with people being killed on a regular basis.

Charley Valera is the author of My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers, which includes photos and personal stories of a dozen more veterans from every branch and both theaters of WWII. Copies are available at Amazon.com and BN.com. Signed copies of the book are available only at www.charleyvalera.com. You can view many of the actual interviews on YouTube at https://goo.gl/4Q1919.