by Bob Sparenberg

I was born in Grimbergen, Belgium in November of 1945 and am the second youngest of three boys and three girls. My family survived 4 years of Nazi occupation. In my early life, I relived the stories of my brothers and sisters fears throughout those years. I listened to my brothers’ stories of dog fights between M109s and Spitfires over our village, as well as, the constant barrage of B17s flying overhead to bomb Germany. My mother explained that when the Germans came into our village, the sound of their goosesteps on the cobblestones could be heard for miles before they even entered Grimbergen. That is when fear gripped the village and they knew what their future would be.

My parents, throughout those years, kept in contact with the Dutch underground in order to assist them whenever needed. They hid in our home, under a carpet which concealed a door on the dining room floor and which was covered by a large table, allied personnel who had been through the night, covertly moved to our home for safe passage out of Belgium. They would then be moved at the most opportune time in the night, to a convent in our village. On several occasions, the Gestapo and the local police who were working for the Nazi regime, entered our home to confront my family. They had heard rumors from local villagers that suspicious activity was going on at the Sparenbergs. My father was a widower when he married my mother. Together, my mother and father had 6 children. However, my father had 3 sons from his first marriage. One of my half-brothers had joined the German army, unbeknownst to the family. In the early part of 1944, my father received a letter on Nazi letterhead, mailed from Russia where my half-brother was fighting against the Russians. This letter proved to be a saving factor for my family being spared from confinement in the local concentration camp or possible execution. One day the Gestapo entered our home and lined my family up against the wall. A black shirt in our village had informed them that the Sparenbergs were possibly helping the enemy. A black shirt was a local villager who sympathized with the Nazis.

It was during this time that my father believed that God spoke to him and told him to get the letter and show them that his son is fighting for the Germans and that they too were in support of Germany. When the Gestapo saw the letter they left them with only a warning. This brought such relief to the family at that time. Several days later they were crawling under the kitchen table as the sound of V2 rockets could be heard whistling overhead. Several months later the Gestapo came back again looking for my father’s other son who they found out had become a Merchant Marine, the opposite of his brother who had joined the Germans. This son was moving supplies throughout the North Sea from England to France. My father was well aware of the dangers connected with war. In WW1 in 1917, he had patrolled the Dutch and Belgian borders on a Harley-Davidson for the Dutch Army in search of deserters between the two countries.

I sometimes reflect back on my brothers’ experiences, one of which was trying to take a 50 caliber machine gun out of a B17 which had crash landed in our village and their failure to do so. However, my oldest brother, Alex, managed to crack off pieces of the cockpit window and carved little B24s out of them which he still has to this day on his living room mantel. In a recent phone conversation with my oldest sister, Betsy, who is now 82, I told her about the men I am working with and the article that I was writing. She said, “Robert, to this day I still have fear. When I see a black PT Cruiser, my mind goes back to the Gestapo who had black sedans with the SS sign and the swastika.” They were the ones who assisted in putting Jewish families from our village, as well as our Jewish neighbors, onto the boxcars which were on the tracks directly across from our home. In the summertime it was hot and humid and there would be days and sometimes weeks with no power. My family would sleep with mosquito nets over their beds. My sister remembers early one morning being awakened by the sound of a German bayonet ripping through her net to see who was sleeping in the bed. They were making sure no Jewish children were being hidden with the local villagers.

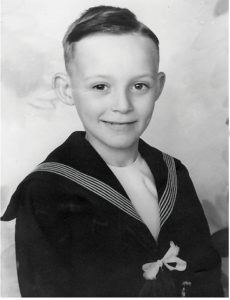

One day, the talk in our village was the Americans had entered the Ardennes and were pushing their way into the Bulge. With Providence on the side of America, the German war machine was running out of fuel and ammunition. They were able to secure approximately 50,000 gallons of fuel from the American fuel depot but this was not enough to feed the thirsty armored division. This could have been a turning point of Germany’s success. After our village was liberated by British soldiers, many of them stayed by combat ready, to assist if needed, in the Bulge. (I was named after one of those British soldiers, Robert Seaman.) The impact of the American soldiers fighting in the Bulge was a crucial point in the history of WW2. It was truly the final liberation of the Belgian Ardennes. It left a deep thankful spirit in the hearts of the Belgian people who consider the Americans their heroes. And this thankfulness is celebrated every year since the Battle of the Bulge. Growing up in a grateful family, my passion has been to meet the men who fought those eighty kilometers from our village.

Five years ago, I received a call from my son who was working at a Senior Center in Texas. He had just finished taking the blood pressure of a 90-year old 3rd army anti-aircraft gunner who was stationed in the Luxembourg Ardennes. Soon after he called me, I was introduced to Richard “Tex” Stanley. Richard was nicknamed “Tex” by General Patton and had survived 6 major battles of WW2. This began a friendship and camaraderie that fueled a passion for meeting other veterans who fought in our little country. I soon discovered I can find them by daily looking, in my travels, for those older men who proudly wear their WW2 Veteran hat, which sets them apart from the crowd. Among them is Ralph Garrett, Sr., age 94, of the 106th infantry. Ralph, another Texas native, came to my attention in a Walmart, wearing a WW2 hat, which invited an introduction on my part. “Thank you for your service, sir! Pacific Theater or European Theater?” This always leads into an interesting conversation which ends up in a lasting friendship. In a recent get together of these vets, I introduced Ralph to D-Day +1, 2nd Infantry, 9th regiment, 100-year old, Master Sergeant Homer Cox. They had never met before and yet on December 16th and 17th of 1944, the 2nd Infantry crossed paths with the 106th. They shared a lot of stories after shaking hands that day.

I am privileged to attend once a month in Ft. Worth, Texas, a Veterans’ luncheon, called “Roll Call”. When my veterans are able to attend, I take them to this free luncheon where as many as 70 plus WW2 veterans and their families attend, along with other veterans. I was honored to speak to this group and asked for a show of hands of those men who fought in Belgium. A number of hands went up and after finishing I had the joy of meeting a number of new friends. Among them is Carmen Gisi, age 94, 101st Airborne Division. Carmen had been back to Bastogne on a number of occasions, by invitation. Again, this Belgian boy felt so privileged to be able to sit down and eat with these men and also call them his friends. And I always tell them in leaving that I am here because they were there.

At 72 years old, each day that goes by is one that I enjoy here in America because they were there in that last great battle which ended the terror of that era and provided the freedom for the whole world to enjoy. Today, my wife and I have made it our mission to seek and to thank the men whose boots plowed the snow and the mud of the Ardennes. Thank God for the American soldier.