V. L. AULD

TIMELINE OF MILITARY SERVICE

IN THE U. S. ARMY

August 1942 to August 1974

Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Enlisted in U.S. Army in August 1942 and spent 17 weeks in basic training at the Field Artillery Training Center. Completed Officer Candidate School graduating in February 1943.

Pittsburg, Kansas

Reported to Pittsburg, Kansas, in February 1943 and completed liaison pilot training, then returned to Fort Sill for the tactical phase of the course.

Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Trained in techniques of short field take offs and landings, one-wheel takeoffs and landings, how to land on roads, how to evade enemy aircraft, and how to fire on targets from the air. On completion of the tactical course for liaison pilot, I was assigned to the 909th Field Artillery Battalion of the 84th Infantry Division.

Camp Howze, Gainesville, Texas

The 84th was being activated at Camp Howze near Gainesville, Texas, where I had completed my pilot training at Gainesville Junior College before enlisting in the Army. The camp had dirt streets and more tar paper buildings like we had at Ft. Sill. I was assigned as the first air officer of the 909th and was given the job as Battalion Air Officer. The Division went through many field exercises and reached its full complement; however, we had to go through the Louisiana Maneuvers to pass certain tests and receive more training.

Louisiana Maneuvers

From Camp Howze, the 84th went to the Louisiana Maneuver Area for eight weeks of large-scale games beginning 19 September 1943. We had our first accident during these maneuvers. Our commanding officer, Major General Stonewall Jackson, was killed 14 October 1943 when flying with a liaison pilot to observe the troops in training. There were several administrative changes made, and our assistant commanding officer, Brigadier General Nelson M. Walker, temporarily replaced General Jackson. However, General Walker was transferred to another unit and moved to Europe for the D-Day Invasion and was killed at Normandy. On 15 June 1944 General A. R. Bolling took command of the 84th Infantry Division and served in that position for the rest of the war.

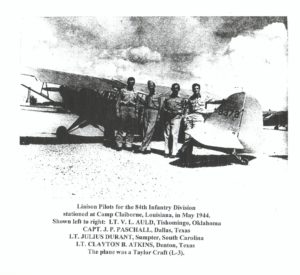

Camp Claiborne, Louisiana

On 15 November 1943, the Division moved to Camp Claiborne, a temporary post close to Fort Polk, Louisiana, and continued to train until August 1944 when they began to prepare for overseas movement.

Camp Kilmer, New Jersey

After orders were received to move overseas, the Division reported to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, then moved to the port of embarkation about 18 September 1944. The 335th Infantry and units of the Division Artillery boarded the Sterling Castle (an English ship). They were in a collision with another ship at sea during the first night out and had to return to port for repairs. The accident ripped a hole in the bow about 40 feet high, and all 7,000 soldiers went back to Camp Kilmer while the ship was being repaired. Then, they re-boarded the ship and headed for England.

South Hampton, England

The Sterling Castle docked at South Hampton, England, and we joined with the Division in the southern part of England. Spent one weekend in London with my brother Joe Auld, who was stationed in England in an Air Force Glider Unit. We managed to get a room in the Savoy Hotel. After cleaning up, we went hunting for a restaurant—finally found one in a basement. About the only thing they had to offer was something made out of powdered eggs (I think), but we were glad to get that. We went exploring and found the famous Piccadilly Square, the Queen’s Palace, and the famous Cathedral. We parted and that was the last time we saw each other in Europe.

During this period, a change in the table of organization was made, and Liaison Pilots became the Air Section of the Division Artillery Headquarters. We were authorized to have a Division Artillery Air Officer and an Assistant, and my job changed from Battalion Air Officer to Assistant Division Artillery Air Officer.

Our aircraft had arrived in England in crates so we assembled the planes and checked them out. We were authorized to have ten liaison airplanes (L-2’s), but we had eleven pilots. Major Paschall, the Division Air Officer, did not want to ride an LST across the English Channel, so we gathered up parts from all over the United Kingdom and put together the eleventh airplane so all could fly across.

Omaha Beach, France

The first units of the 84th Division landed on Omaha Beach, France, on 1 November 1944 with the remainder arriving the next three days. An English amphibious plane accompanied us across the Channel, and my plane began to smoke during the flight. That made for an exciting trip, but no fire broke out. The smoke came from some heaving packing grease on the engine that did not get removed before assembling the plane.

We found the Germans had put up long polls (about 8 feet in height) on the beach to prevent planes and gliders from landing, so we landed on a road. My flight was to a strip called A-23 that was on the Cherbourg Peninsula. The wind was too strong for my plane to land so two jeeps were sent out to help; they ran along beside me and grabbed my struts to pull me down.

Gulpen, Belgium

The 84th Division moved through France into Belgium and Holland in record time; most of the Division spent less than 48 hours in France. Our units were put into the line somewhere near the little village of Gulpen, Belgium, and the Liaison Pilots were given the assignment to fly and orient themselves in finding our front lines and observing the enemy.

Siegfried Line

After our initial assignment, the 84th Division became a part of the Ninth Army. We worked with the British, the 2nd Armored, and the 102nd Infantry Division during the capture of our section of the famous Siegfried Line. It was a tough job to crack, and we finally had to use flame throwers and direct fire to destroy the pill boxes. According to Lt. Theodore Draper’s book, THE 84TH INFANTRY DIVISION IN THE BATTLE OF GERMANY, it took seventeen days from 16 November to 2 December 1944.

Aachen (located on the famed Siegfried Line) was extremely important strategically and was considered to be the doorway to the heart of Germany. In flying our sector we could see Aachen and Geilenkirchen from the air. Our 333rd and 334th combat teams were assigned to start the campaign, and Geilenkirchen was taken in about ten days. According to history, Geilenkirchen was secured between 18 and 24 November 1944.

I was flying in the vicinity of Geilenkirchen when I was shot. A round came through the bottom of the fuselage and hit me in the lower back. I managed to get my plane behind our lines, spotted an aid station, and landed. Lt. Bonnett, my observer, assisted in getting me out of the plane and took me to the 91st Evacuation Hospital where I spent about three days. The war would have been over for me if it had not been for my persistence to return to my group; Sergeant Harrington, a native of Henderson, Texas, came to pick me up. On returning to duty, I found my fellow pilots had obtained “stove lids” to sit on to protect their hind parts; I slept on my stomach for several nights. I was the first in my unit to get hit but not the last.

The 2nd Armored Division encountered the 9th Panzer Division on or about 17 November. They were on our right flank, and I happened to be flying a regular mission when the German tanks came to my attention. Under normal procedure, we would adjust on a tank and fire for effect. That was probably about three volleys of battalion fire, or 36 rounds. In this case, however, more tanks came into my field of fire, and I was reporting them as fast as I could plot them on a map.

Unknown to me this battle was raging and our armor was no match for the tiger tank. The Division Artillery S3 came on the air and told me to fire the whole Division Artillery on the tanks until they told me to stop. This turned out to be a serious threat to the 2nd Armored Division and possibly to our right flank.

For the better part of my flight, I was firing 36 guns at a time on these tanks. The best the 105 Howitzers could do would be to make them button up and hope for a lucky hit, but we did help the 2nd Armored Division get into position to get direct hits on the German tanks and win the battle. This was the largest, longest, and continuous fire mission that I believe I directed.

After breaching the Siegfried Line, the next major obstacle for the 84th was the crossing of the Roer River which proved to be quite an obstacle. We were closing in on the Roer on 16 December 1944 when the Germans launched their biggest offensive in the battle of Western Europe known as the Battle of the Bulge. We continued to accomplish our objective in our assigned sector, and our planes would fly over the front lines from daylight till dark looking for targets and communicating with our Infantry.

Our planes were popular targets for the Germans because they knew we could observe their movement. We could adjust on them faster than our observers on the ground; our position in the air added a third dimension to the adjustment. They shot at us with just about everything they had from rifle fire to 88mm cannons and mortar fire.

Marche and Hotton, Belgium

Around 18 or 19 December 1944, the 84th Division was ordered to take up positions around Marche, Belgium, and establish a line of defense between Marche and Hotton. I took the Air Section’s only 6-by-6 truck and three or four of our crew, and we joined the advance party to go south toward the Ardennes in search of our front line. We arrived just outside the town of Marche at the same time some German tanks drove up to the outskirts of Marche from another direction. They did drop a few rounds on the town, but, fortunately for us, they were not daring enough to enter the town. By the next morning, elements of our Division started rolling in. The troop shortage was so bad that even our Division Commander General Bolling was directing traffic.

On 21 December 1944, I took my crew and truck, and we back tracked about 2000 yards looking for a landing strip. The terrain was hilly and covered with snow, but we finally found a place on the side of a hill. We had to land by putting the plane into a slip over a bunch of tall popular trees so it was a tricky place to land and take off.

The night before our planes arrived from the Geilenkirchen area, there was a tank battle down on the other side of the hill from our selected air strip. It turned out that this battle was the farthest point the Germans were able to penetrate during the Battle of the Bulge. It was the 24th of December, and my small crew and I were very grateful when the tank battle was over. After our planes arrived and we set up our schedule, we began to fly the line between Marche and Hotten, and I recall flying the line on Christmas Day.

We moved our air strip several times during the Battle of the Bulge, and, at one point, we had moved back from the front to a place just outside of Liege, Belgium. We occupied a chateau with about 20 bedrooms, and it turned out to be right in the line of fire of the buzz bombs. The Germans were trying to hit our big ammunition dump close to Liege. They never did, but one bomb landed about 15 feet from my plane and twisted it up like you twist a newspaper.

As the battle continued, we had to move along to be accessible to the troops. Generally, we fought toward Bastogne which was the area where the Germans had the 101st Airborne Division bottled up. This is the famous place where the Germans had sent a messenger to tell the Commanding General Anthony McAuliffe to give up. The General sent back his answer: “Nuts.” As we were gradually pinched off by the 3rd Army on the right and other troops on our left, we were relieved to return to our positions in the north part of Germany in the vicinity of Geilenkirchen and the Roer River.

Roer River

Now our attention had to be returned to crossing the Roer River which varied in width from 60 to 260 feet and from 2 to 12 feet deep. The Germans managed to open the gates of the Hemback Dam and blow up Erft Reservoir, so the Roer was at its maximum height and width for about all of February.

The Air Section resumed the job of flying the front and engaging targets of opportunity or on any targets we might be directed to fire on by the Fire Direction Center of the Division Artillery, or of one of the Battalions. By doing this, we helped to force the enemy to keep their movements to a minimum. The 84th Artillery and our attached Battalions, which at times were as many as 36 battalions, pounded the far side of the Roer to prepare the way for our eventual crossing. The forward observers and air observers made it very costly for Germans to move around. The Infantry crossed the Roer under cover of darkness so we could not fly across, but we had helped to soften up the enemy during the daytime preparations.

Once we had our Infantry across the Roer, we moved in a generally north direction. From the Roer to the Rhine, it was move, shoot, and communicate, and we moved our air strip several times reaching the Rhine River about 5 March 1945.

Rhine River

Our front became the Rhine River, and we flew this path every day. We shot at everything that moved on the other side of the river for about a month while our Infantry rested. We were located directly across the Rhine from Duisburg. Dusseldorf was just south of Duisburg, and the whole east side in this area was industrial. Every time a train would try to move during the day time, we would fire on it with our Artillery.

Our Division did not have the job of establishing the bridgehead on the other side of the Rhine. The 79th Infantry did that for us, so our Division crossed in the day time on the pontoon bridge established by the engineers.

Elbe River

The plan was for the 5th Armored to drive toward the Elbe River with the 84th close behind to clean up any pockets of resistance, but we still had to cross the Weser River before the Elbe.

General Eisenhower had ordered leaflets to be dropped with a message that if the Germans would display white flags, we would not shoot up their villages. As my observer and I were flying well beyond the leading elements of our troops to determine compliance with his request, I spotted the Weser River. We flew up over the river, and I had quite an eerie feeling about the territory down below. Just as I banked the plane to turn around, we caught a concentration of machine gun fire. I straightened up the plane and pushed forward on the stick to go down to a lower altitude, but nothing happened. They had shot out my elevator cables. Fortunately, I thought about the trim tab and used it to maneuver the plane.

When they hit us a second time, they knocked out our radio, and my observer got hit with several pieces of metal in the back of his head. How they managed to miss me, I’ll never know. I guess that fellow upstairs decided it wasn’t my time. The plane was damaged badly and could hardly fly, so I started looking for a place to land. I eased the plane down using the trim tab, helped the observer out, and we walked over to a small civilian hospital (German). Luck was still with us as no German soldiers were around, and the hospital personnel took care of my observer. Then, we started walking down the road toward our lines. After a while, a jeep came along and took us back to our air strip.

As the Division moved up to the Weser River, the front stabilized for a few days. Hanover came into view from the air, and the enemy was defending more vigorously since the river gave them a good barrier. We pushed across the Weser and to the outlying area of Hanover. After we took Hanover and passed it by, our air strips were being moved forward toward the Elbe River. Near each air strip selected, we found German POW Camps and camps for displaced persons who were literally starving to death.

After we moved up close to the Elbe, a large building came into view and a large sign on the building disclosed that it was a Singer Sewing Machine manufacturing plant. I believe it was the town of Willenburg on the east side of the Elbe. General Eisenhower had made an agreement with the Russian Command to allow the Russians to take the territory on the other side of the river, so we sat there for several days since we beat them to the Elbe.

Heidelberg, Germany

The war was over for us about 8 May 1945. Our Division was moved to an area near Heidelberg, Germany, and we began a phase of military occupation while higher headquarters established guidelines on who would go home. For our occupation duty, the Air Section became a courier service, more or less. The 7th Army Headquarters had moved into Heidelberg so it became a busy place. I also worked with the local mayor (burgomaster) to settle problems between the civilians and the soldiers in our Air Section.

Marseilles, France

Finally, it came my time in November 1945 to start back to the States, and I was assigned about 200 men. We were sent to Frankfort, Germany, where we boarded boxcars (forty and eights) and headed for Marseilles, France. On the trip we were put on a railroad siding in Lyon, France, and sat there for about a day and a half. The little children would crowd around and beg for food, chocolate, and cigarettes. Sometime after reaching the camp just north of Marseilles, we moved to the port and boarded a ship for home.

Mediterranean Sea

We moved through the Mediterranean Sea during darkness, and I could see the northern shore of Algeria and Morocco and the lights of the towns along the shores. We moved through the Strait of Gibraltar and headed for New York and back to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey.

Camp Kilmer, New Jersey

Finally, at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, I was assigned at least 200 more troops for a train trip to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, for separation from active duty. After a short stay at Camp Chaffee and some more paper work, I boarded a civilian bus for the final leg of my journey home.

Tishomingo, Oklahoma

I arrived home in time for Christmas 1945 and went to work with my parents, Virgil and Jeanette Auld, in the dry cleaning business in Tishomingo, Oklahoma.

Oklahoma National Guard

In February 1946, I was officially relieved from active duty having achieved the rank of Captain.

The Army was still high on my agenda, so it wasn’t long before I was headed for Oklahoma City and the 45th Infantry Division Headquarters. The 45th Reconnaissance Troop was being reactivated in Tishomingo as part of the National Guard for the State of Oklahoma, and I was given the assignment as Commander for the next four years.

Army Active Reserve

In the fall of 1950, I was relieved as the Commander of the Reconnaissance Troop in order to continue my education at the University of Oklahoma. At that time, I was transferred to the Army Active Reserve and was promoted to Major since I had been a Captain for 5 ½ years.

From the time that I entered college as a full-time student in 1950 until my retirement in 1974, I served in various reserve schools, completed the Advanced Artillery Course, the Command and General Staff College, the Adjutant General Course, and other short courses. As I completed these various courses, I was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and then Colonel.

I attended summer camps at various places every year serving as an instructor several times. I worked in the Adjutant General’s Office at the Forrestal Building in Washington, D. C., for three summers. Since I enlisted on 12 August 1942 and was retired in 1974, I was credited with 32 years of active and reserve time.

I had the privilege of serving at the following posts, camps, and stations in the United States:

- Fort Sill, Oklahoma

- Pittsburg, Kansas

- Camp Howze, Texas

- Camp Claiborne, Louisiana

- Fort Polk, Louisiana

- Camp Kilmer, New Jersey

- Fort Chaffee, Arkansas

- Fort Bliss, Texas

- Fort Lewis, Washington

- Camp McCoy, Wisconsin

- Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

- Fort Meyers, Virginia

- Fort McNair, Virginia

- Office of Adjutant General, U.S. Army Administration Center, St. Louis, Missouri

- Office of Adjutant General, Forrestal Building, Washington, D.C.

In addition, I worked at armories located in Tishomingo, Oklahoma; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Lafayette, Louisiana.

Service Recognition

During World War II, Liaison Pilots were awarded an Air Medal for 36 missions or sorties to the front line to do their job of directing fire for the Artillery and reporting targets of opportunity and other information observed while on a mission. I completed 123 missions during the European Theater and was awarded three Air Medals.

In addition, I was shot while on a mission somewhere over Geilenkirchen and was awarded the Purple Heart. Other awards I received for service were: European Theater Ribbon with Three Battle Stars, European Occupation Ribbon, and the Good Conduct Medal.

Story and photos submitted by Lorene Auld, Associate and wife of V. L. Auld