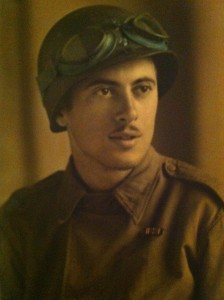

My father, Anthony John Capozzoli was 18 when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in February 1943, the fourth son to go in his family. He left his job at Temple Music in Rockville Center, Long Island, New York, and reported to Camp Upton, located in Suffolk County, Long Island, for a few days.

He travelled by train to Camp McCain, MS where he was assigned to Headquarters Company 346th Infantry Regiment for several weeks. “The barracks were made of packing crates with tar paper over them. There were 2 potbelly stoves you were assigned to maintain. It was the middle of winter down there,” he explained.

From there he went to Fort Bragg, NC for a few months. “We went out on maneuvers —learning how to fight—going under barbed wire with real machine guns firing over you—role playing as if you were in combat,” he told me. He had the job of cleaning the latrines while there, a job that kept him in a warm location.

This training was followed by a 6-month stint at Fort Benning, GA. where he attended school to learn Morse Code. “We would get up about 3 o’clock in the morning, have breakfast, then we went to an area where we sat at a table, put earphones on and practiced Morse Code. We had to read what you heard,” he said.

With training in communications as a radio operator, he went back to Fort Bragg to join the rest of his company. He, along with other members of the 87th Infantry Division, boarded the Queen Mary in October 1944 and travelled to Scotland on a 4-day voyage. They stayed in Scotland until their equipment arrived. He drove a big truck down to Dover, England with the rest of the convoy. “I had never driven a truck in my life,” he noted.

The 87th Infantry Division crossed the English Channel on a liberty ship and arrived in LeHavre, France, in November of 1944. As part of the 87th, he travelled through France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany mostly by Jeep. The mission was specific, where “whenever we got to a town, we would cut the lines of communication and set up our own.” He explained that: “We camped in houses when we took over a town” noting that “our communications people were behind the infantry.” They knew they were supporting the troops, but “we did not know what we were sending because it was in code. The message center would decode it after it arrived.”

Dad participated in campaigns in the Ardennes, the Rhineland, and in the Battle of the Bulge as part of Patton’s Third Army. During this battle, he assisted in keeping wire communications for the 346th HQ Company of the 87th Division. He recalls going as far as Yugoslavia before stopping so that the Russians could come in and occupy part of Germany. At this point, the war in Europe had finally ended.

He went back to Germany where they were assigned to a camp while waiting to sail home. Upon his return to the U.S., he was on furlough for 30 days during August 1945, awaiting assignment to fight the Japanese in the Pacific. But the war ended.

Because Anthony did not have enough points to be discharged, he was sent from Boston where their ship landed, to Sandy Hook, NJ, which was a reception center for new recruits. Here his job was handing out uniforms. Whenever possible, he went home on weekends by boat to Brooklyn and from there, by train back to Freeport, NY.

After his discharge, Anthony returned home to Freeport, resumed his job, and attended New York Radio Institute in New York City at night. He married Joan Michalicki in 1950. They settled in Merrick 5 years later. Until his retirement in 1989, he owned his own business as a television/radio technician. He moved to Sebastian, FL in 1991. This year he celebrated his 90th birthday there with family and friends.

After his discharge, Anthony returned home to Freeport, resumed his job, and attended New York Radio Institute in New York City at night. He married Joan Michalicki in 1950. They settled in Merrick 5 years later. Until his retirement in 1989, he owned his own business as a television/radio technician. He moved to Sebastian, FL in 1991. This year he celebrated his 90th birthday there with family and friends.

Submitted by Mary Jane Capozzoli-Ingui